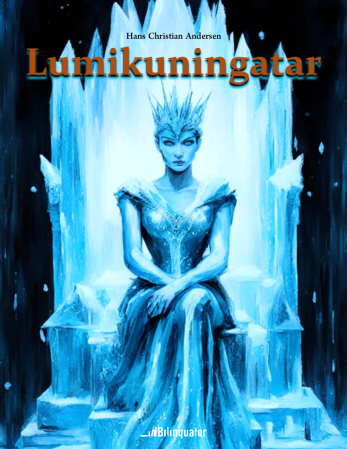

Фінска-англійская кніга-білінгва

Hans Christian Andersen

Lumikuningatar

Hans Christian Andersen

The Snow Queen

Translator: Maila Talvio. From The Project Gutenberg. Seitsentarinainen satu. Vilhelm Pedersenin kuvituksella.

Translated by Mrs. H. B. Paull. With illustrations of Vilhelm Pedersen

Ensimäinen tarina kertoo peilistä ja sirpaleista

Story the First, Which Describes a Looking-Glass and the Broken Fragments

Kas niin, nyt me alamme. Kun olemme päässeet tarinan loppuun, tiedämme enemmän kuin me nyt tiedämme, sillä oli paha peikko — se oli kaikkein pahimpia peikkoja, se oli ”Perkele”.

You must attend to the commencement of this story, for when we get to the end we shall know more than we do now about a very wicked hobgoblin; he was one of the very worst, for he was a real demon.

Eräänä päivänä oli hän oikein hyvällä tuulella, sillä hän oli tehnyt peilin, jolla oli se ominaisuus, että kaikki hyvä ja kaunis, mikä siihen kuvastui, hävisi siinä miltei olemattomiin, mutta mikä oli kelvotonta ja näytti rumalta, se astui esiin ja kävi vieläkin pahemmaksi.

One day, when he was in a merry mood, he made a looking-glass which had the power of making everything good or beautiful that was reflected in it almost shrink to nothing, while everything that was worthless and bad looked increased in size and worse than ever.

Kauneimmat maisemat olivat siinä keitetyn pinaatin näköiset ja parhaimmat ihmiset kävivät inhoittaviksi tai seisoivat päällään, ilman vatsaa. Kasvot vääntyivät niin, ettei niitä tuntenut ja jos ihmisessä oli kesakko, sai olla varma siitä, että se levisi nenän ja suun yli.

The most lovely landscapes appeared like boiled spinach, and the people became hideous, and looked as if they stood on their heads and had no bodies. Their countenances were so distorted that no one could recognize them, and even one freckle on the face appeared to spread over the whole of the nose and mouth.

Se oli erinomaisen huvittavaa, sanoi ”Perkele”. Jos hyvä harras ajatus kävi läpi ihmisen mielen, tuli peiliin sellainen irvistys, että peikkoperkeleen piti nauraa taitavaa keksintöään.

The demon said this was very amusing. When a good or pious thought passed through the mind of any one it was misrepresented in the glass; and then how the demon laughed at his cunning invention.

Kaikki ne, jotka kävivät peikkokoulua — sillä hän piti peikkokoulua — kertoivat laajalti, että oli tapahtunut ihme. Vasta nyt, arvelivat he, saattoi oikein nähdä, miltä maailma ja ihmiset näyttävät.

All who went to the demon’s school—for he kept a school—talked everywhere of the wonders they had seen, and declared that people could now, for the first time, see what the world and mankind were really like.

He juoksuttivat peiliä ympäri maailman ja vihdoin ei ollut yhtään maata eikä ihmistä, joka ei olisi siinä vääristetty.

They carried the glass about everywhere, till at last there was not a land nor a people who had not been looked at through this distorted mirror.

Nyt tahtoivat he myöskin lentää ylös taivasta kohti, tehdäkseen pilkkaa itse enkeleistäkin ja ”Jumalasta”. Kuta korkeammalle he peiliä lennättivät, sitä voimakkaammin se nauroi, tuskin he voivat pitää siitä kiinni. Yhä korkeammalle ja korkeammalle he lensivät, likemmä Jumalaa ja enkeleitä.

They wanted even to fly with it up to heaven to see the angels, but the higher they flew the more slippery the glass became, and they could scarcely hold it, till at last it slipped from their hands, fell to the earth, and was broken into millions of pieces.

Silloin värisi peili nauraessaan niin hirvittävästi, että se karkasi niiden käsistä ja syöksyi alas maahan, missä se meni sadaksi miljoonaksi, biljoonaksi ja vielä useammaksi kappaleeksi, ja nyt se tuotti paljoa suurempaa onnettomuutta kuin ennen.

But now the looking-glass caused more unhappiness than ever, for some of the fragments were not so large as a grain of sand, and they flew about the world into every country.

Sillä muutamat kappaleet olivat tuskin hiekkajyvästen kokoiset ja nämä lensivät ympäri maailmaa, ja missä ne sattuivat ihmisten silmiin, siellä ne pysähtyivät sinne ja silloin näkivät nuo ihmiset kaikki vääristettynä ja heillä oli silmää nähdä vain se, mikä jossakin asiassa oli nurjaa, sillä jokainen pieni peilinsärö oli säilyttänyt saman voiman, mikä koko peilillä oli.

When one of these tiny atoms flew into a person’s eye, it stuck there unknown to him, and from that moment he saw everything through a distorted medium, or could see only the worst side of what he looked at, for even the smallest fragment retained the same power which had belonged to the whole mirror.

Muutamat ihmiset saivat vielä sydämeensä pienen pellinpalasen ja se oli varsin kauheaa, siitä sydämestä tuli kuin jääkimpale.

Some few persons even got a fragment of the looking-glass in their hearts, and this was very terrible, for their hearts became cold like a lump of ice.

Muutamat peilinkappaleet olivat niin suuret, että ne käytettiin ikkunalaseiksi, mutta sen ruudun läpi ei ollut hyvä katsella ystäviään.

A few of the pieces were so large that they could be used as window-panes; it would have been a sad thing to look at our friends through them.

Muutamat palaset joutuivat silmälaseihin, ja huonosti kävi, kun ihmiset panivat ne nenälleen oikein nähdäkseen ja ollakseen oikeamieliset. Paholainen nauroi niin, että hänen vatsansa repesi ja se kutkutti häntä niin suloisesti.

Other pieces were made into spectacles; this was dreadful for those who wore them, for they could see nothing either rightly or justly. At all this the wicked demon laughed till his sides shook—it tickled him so to see the mischief he had done.

Mutta ulkona lenteli vielä ilmassa pieniä lasisirpaleita. Nyt me saamme kuulla!

There were still a number of these little fragments of glass floating about in the air, and now you shall hear what happened with one of them.

Toinen tarina. Pieni poika ja pieni tyttö

Second Story: A Little Boy and a Little Girl

Suuressa kaupungissa, missä on niin monta taloa ja ihmistä, ettei jää tarpeeksi tilaa jokaisen saada pientä puutarhaa ja missä sentähden useimpien täytyy tyytyä kukkasiin kukkaruukuissa — siellä oli kuitenkin kaksi köyhää lasta, joilla oli jonkun verran suurempi puutarha kuin kukkaruukku.

In a large town, full of houses and people, there is not room for everybody to have even a little garden, therefore they are obliged to be satisfied with a few flowers in flower-pots. In one of these large towns lived two poor children who had a garden something larger and better than a few flower-pots.

He eivät olleet veli ja sisar, mutta he pitivät yhtä paljon toisistaan kuin jos olisivat olleet sitä.

They were not brother and sister, but they loved each other almost as much as if they had been.

Vanhemmat asuivat aivan lähellä toisiaan, he asuivat kahdessa ullakkokamarissa. Siinä, missä katto toisen naapurin talosta sattui yhteen toisen kanssa ja vesikouru kulki pitkin katonrajaa, siinä antoi molemmista taloista ulos pieni ikkuna.

Their parents lived opposite to each other in two garrets, where the roofs of neighboring houses projected out towards each other and the water-pipe ran between them.

Ei tarvinnut muuta kuin asettua hajareisin kourulle, niin pääsi toisesta ikkunasta toiseen.

In each house was a little window, so that any one could step across the gutter from one window to the other.

Molemmat vanhemmat pitivät ulkona suurta puulaatikkoa ja siinä kasvoi kyökkikasveja, joita he tarvitsivat, ja pieni ruusupuu. Kummassakin laatikossa oli yksi, se kasvoi niin kauniisti.

The parents of these children had each a large wooden box in which they cultivated kitchen herbs for their own use, and a little rose-bush in each box, which grew splendidly.

Nyt keksivät vanhemmat asettaa laatikot sillä tavalla poikkipäin yli kourun, että ne miltei ulottuivat toisesta ikkunasta toiseen ja aivan muistuttivat kahta kukkalavaa.

Now after a while the parents decided to place these two boxes across the water-pipe, so that they reached from one window to the other and looked like two banks of flowers.

Herneenvarret riippuivat alas laatikkojen yli ja ruusupuut kasvoivat pitkiä oksia, kietoutuivat ikkunoiden ympäri, kumartuivat toisiaan vastaan: siinä oli miltei kuin vihannasta ja kukkasista tehty kunniaportti.

Sweet-peas drooped over the boxes, and the rose-bushes shot forth long branches, which were trained round the windows and clustered together almost like a triumphal arch of leaves and flowers.

Kun laatikot olivat hyvin korkeat ja lapset tiesivät, etteivät he saaneet nousta niille, niin saivat he usein luvan astua ulos toistensa luo, istua pienillä jakkaroillaan ruusujen alla, ja siellä he nyt hauskasti leikkivät.

The boxes were very high, and the children knew they must not climb upon them, without permission, but they were often, however, allowed to step out together and sit upon their little stools under the rose-bushes, or play quietly.

Talvellahan se ilo oli ohi. Ikkunat olivat usein aivan jäässä, mutta sitten he lämmittivät kuparirahoja uunissa, asettivat kuuman rahan jäätyneelle ruudulle ja niin tuli siitä oivallinen tirkistysreikä, ihan pyöreä, ihan pyöreä. Sen takaa katseli suloinen lempeä silmä, yksi kummastakin ikkunasta. Ne olivat pieni poika ja pieni tyttö.

In winter all this pleasure came to an end, for the windows were sometimes quite frozen over. But then they would warm copper pennies on the stove, and hold the warm pennies against the frozen pane; there would be very soon a little round hole through which they could peep, and the soft bright eyes of the little boy and girl would beam through the hole at each window as they looked at each other.

Pojan nimi oli Kai ja tytön nimi Gerda.

Their names were Kay and Gerda.

Kesällä saattoivat he yhdellä hyppäyksellä päästä toistensa luo, talvella täytyi heidän ensin kulkea monet portaat alas ja monet portaat ylös. Ulkona tuiskutti lunta.

In summer they could be together with one jump from the window, but in winter they had to go up and down the long staircase, and out through the snow before they could meet.

— Valkeat mehiläiset parveilevat, sanoi vanha isoäiti.

“See there are the white bees swarming,” said Kay’s old grandmother one day when it was snowing.

— Onko niillä myöskin mehiläiskuningatar? kysyi pieni poika, sillä hän tiesi, että oikeiden mehiläisten joukossa on sellainen.

“Have they a queen bee?” asked the little boy, for he knew that the real bees had a queen.

— On niillä, sanoi isoäiti. — Hän lentää siellä, missä ne parveilevat sakeimmillaan. Hän on suurin heistä kaikista eikä hän koskaan pysähdy maahan, hän lentää takaisin ylös mustaan pilveen. Monena talviyönä lentää hän läpi kaupungin katujen ja kurkistaa sisään ikkunoista, ja silloin ne jäätyvät niin kummallisiksi, ikäänkuin niissä olisi kukkasia.

“To be sure they have,” said the grandmother. “She is flying there where the swarm is thickest. She is the largest of them all, and never remains on the earth, but flies up to the dark clouds. Often at midnight she flies through the streets of the town, and looks in at the windows, then the ice freezes on the panes into wonderful shapes, that look like flowers and castles.”

— Niin, sen minä olen nähnyt, sanoivat molemmat lapset ja sitten he tiesivät, että se oli totta.

“Yes, I have seen them,” said both the children, and they knew it must be true.

— Saako lumikuningatar tulla tänne sisään? kysyi pieni tyttö.

“Can the Snow Queen come in here?” asked the little girl.

— Tulkoon vain, sanoi poika, — niin minä panen hänet lämpöiselle kaakeliuunille ja sitten hän sulaa.

“Only let her come,” said the boy, “I’ll set her on the stove and then she’ll melt.”

Mutta isoäiti silitti hänen hiuksiaan ja kertoi toisia tarinoita.

Then the grandmother smoothed his hair and told him some more tales.

Illalla, kun pieni Kai oli kotona ja puoleksi riisuttuna, nousi hän tuolille ikkunan luona ja katseli ulos pienestä reiästä. Pari lumihiutaletta putosi siellä ulkona ja yksi näistä, kaikkein suurin, jäi toisen kukkalaatikon laidalle. Lumihiutale kasvoi kasvamistaan, vihdoin siitä tuli kokonainen nainen, puettuna hienoimpaan valkoiseen harsoon, joka oli kuin kokoonpantu miljoonista tähdentapaisista untuvista.

One evening, when little Kay was at home, half undressed, he climbed on a chair by the window and peeped out through the little hole. A few flakes of snow were falling, and one of them, rather larger than the rest, alighted on the edge of one of the flower boxes. This snow-flake grew larger and larger, till at last it became the figure of a woman, dressed in garments of white gauze, which looked like millions of starry snow-flakes linked together.

Hän oli kovin kaunis ja hieno, mutta jäästä, häikäisevästä, kimmeltävästä jäästä. Kuitenkin oli hän elävä. Silmät tuijottivat kuin kaksi kirkasta tähteä, mutta niissä ei ollut mitään rauhaa tai lepoa.

She was fair and beautiful, but made of ice—shining and glittering ice. Still she was alive and her eyes sparkled like bright stars, but there was neither peace nor rest in their glance.

Hän nyökkäsi ikkunaan päin ja viittasi kädellään. Pieni poika pelästyi ja hyppäsi alas tuolilta. Silloin tuntui siltä, kuin suuri lintu olisi ulkopuolella lentänyt ikkunan ohitse.

She nodded towards the window and waved her hand. The little boy was frightened and sprang from the chair; at the same moment it seemed as if a large bird flew by the window.

Seuraavana päivänä tuli kirkas pakkanen — ja sitten tuli suoja ja sitten tuli kevät. Aurinko paistoi, vihanta pilkisti esiin, pääskyset tekivät pesää, ikkunat avattiin ja pienet lapset istuivat taas pienessä puutarhassaan korkealla katonräystäällä kaikkien kerrosten päällä.

On the following day there was a clear frost, and very soon came the spring. The sun shone; the young green leaves burst forth; the swallows built their nests; windows were opened, and the children sat once more in the garden on the roof, high above all the other rooms.

Ruusut kukkivat sinä kesänä aivan erinomaisesti. Pieni tyttö oli oppinut virren ja siinä luettiin ruusuista ja niitä ruusuja ajatellessa ajatteli hän omiaan. Ja hän lauloi sen pienelle pojalle, ja poika lauloi sen niinikään:

How beautiful the roses blossomed this summer. The little girl had learnt a hymn in which roses were spoken of, and then she thought of their own roses, and she sang the hymn to the little boy, and he sang too:—

Ruusuja laaksossa hohtaa,

rakas Jeesus siell’ lapset kohtaa.

“Roses bloom and cease to be,

But we shall the Christ-child see.”

Ja pienokaiset pitelivät toisiaan kädestä, suutelivat ruusuja ja katselivat Jumalan kirkkaaseen auringonpaisteeseen ja puhelivat sille, ikäänkuin Jeesuslapsi olisi ollut siinä.

Then the little ones held each other by the hand, and kissed the roses, and looked at the bright sunshine, and spoke to it as if the Christ-child were there.

Ihania suvipäiviä ne olivat, suloista oli olla ulkona raikkaiden ruusupuiden luona, jotka eivät koskaan näyttäneet aikovan lakata kukkimasta.

Those were splendid summer days. How beautiful and fresh it was out among the rose-bushes, which seemed as if they would never leave off blooming.

Kai ja Gerda istuivat ja katselivat kuvakirjaa, jossa oli eläimiä ja lintuja. Silloin — kello löi juuri viisi suuressa kirkontornissa — sanoi Kai: Ai, minun sydämeeni pisti! Ja nyt tuli jotakin silmääni.

One day Kay and Gerda sat looking at a book full of pictures of animals and birds, and then just as the clock in the church tower struck twelve, Kay said, “Oh, something has struck my heart!” and soon after, “There is something in my eye.”

Pieni tyttö tarttui häntä kaulaan. Kai siristeli silmiään: ei, ei mitään voinut nähdä.

The little girl put her arm round his neck, and looked into his eye, but she could see nothing.

— Minä luulen, että se on poissa! sanoi hän. Mutta se ei ollut poissa.

“I think it is gone,” he said. But it was not gone;

Se oli juuri yksi noita lasisirpaleita, jotka lensivät peilistä, taikapeilistä — me kyllä muistamme tuon ilkeän lasin, joka teki, että kaikki suuri ja hyvä, joka kuvastui siinä, kävi pieneksi ja rumaksi, mutta paha ja huono astui oikein esiin ja jokainen vika kävi heti huomattavaksi.

it was one of those bits of the looking-glass—that magic mirror, of which we have spoken—the ugly glass which made everything great and good appear small and ugly, while all that was wicked and bad became more visible, and every little fault could be plainly seen.

Kai raukka, hän oli saanut sirpaleen myöskin suoraan sydämeensä. Pian se oli käyvä ikäänkuin jäämöhkäleeksi.

Poor little Kay had also received a small grain in his heart, which very quickly turned to a lump of ice.

Nyt ei enää tehnyt kipeää, mutta siellä se oli.

He felt no more pain, but the glass was there still.

— Miksi sinä itket? kysyi hän. — Silloin sinä olet ruman näköinen.

Eihän minua mikään vaivaa. Hyi! huusi hän samassa, — tuo ruusu tuossa on madon syömä! Ja kas, tuo tuossahan on aivan viisto! Ne ovat todella ilkeitä ruusuja. Muistuttavat ihan laatikoita, joissa kasvavat. Ja sitten hän jalallaan lujasti tönäisi laatikkoa ja repäisi pois molemmat ruusut.

“Why do you cry?” said he at last; “it makes you look ugly. There is nothing the matter with me now. Oh, see!” he cried suddenly, “that rose is worm-eaten, and this one is quite crooked. After all they are ugly roses, just like the box in which they stand,” and then he kicked the boxes with his foot, and pulled off the two roses.

— Kai, mitä sinä teet! huusi pieni tyttö, ja kun hän näki hänen kauhunsa, repi hän irti vielä yhden ruusun ja juoksi sitten sisään omasta ikkunastaan, pois herttaisen pienen Gerdan luota.

“Kay, what are you doing?” cried the little girl; and then, when he saw how frightened she was, he tore off another rose, and jumped through his own window away from little Gerda.

Kun Gerda sitten tuli ja toi kuvakirjan, sanoi hän, että se oli sylilapsia varten. Ja jos isoäiti kertoi satuja, niin pani hän aina joukkoon ”mutta” — niin, jos hän vain saattoi päästä likettyville, niin kulki hän hänen perässään, pani silmälasit nenälleen ja puhui niinkuin hän. Se oli aivan kuin olisi ollut isoäiti, ja sitten ihmiset nauroivat häntä.

When she afterwards brought out the picture book, he said, “It was only fit for babies in long clothes,” and when grandmother told any stories, he would interrupt her with “but;”. Or, when he could manage it, he would get behind her chair, put on a pair of spectacles, and imitate her very cleverly, to make people laugh.

Pian hän osasi matkia kaikkien ihmisten puhetta ja käyntiä koko sillä kadulla.

By-and-by he began to mimic the speech and gait of persons in the street.

Kaikkea, mikä heissä oli erikoista eikä kaunista, sitä osasi Kai jäljitellä, ja sitten sanoivat ihmiset: sillä pojalla on varmaan erinomainen pää! Mutta se johtui siitä lasisirpaleesta, jonka hän oli saanut silmäänsä, siitä lasisirpaleesta, joka oli sydämessä. Sentähden kiusasi hän pientä Gerdaakin, joka koko sielustaan piti hänestä.

All that was peculiar or disagreeable in a person he would imitate directly, and people said, “That boy will be very clever; he has a remarkable genius.” But it was the piece of glass in his eye, and the coldness in his heart, that made him act like this. He would even tease little Gerda, who loved him with all her heart.

Hänen leikkinsä kävivät nyt aivan toisenlaisiksi kuin ennen, ne olivat niin järkevät. Eräänäkin talvipäivänä, kun lumihiutaleita tuprutti, tuli hän, kädessään suuri polttolasi, piteli levällään sinistä takinlievettään ja antoi lumihiutaleiden pudota sille.

His games, too, were quite different; they were not so childish. One winter’s day, when it snowed, he brought out a burning-glass, then he held out the tail of his blue coat, and let the snow-flakes fall upon it.

— Katso nyt lasiin, Gerda, sanoi hän ja jokainen lumihiutale tuli paljon suuremmaksi ja oli komean kukan tai kymmensärmäisen tähden näköinen. Se oli kaunista katsella.

“Look in this glass, Gerda,” said he; and she saw how every flake of snow was magnified, and looked like a beautiful flower or a glittering star.

— Näetkö, kuinka taidokasta! sanoi Kai. — Se on paljon mielenkiintoisempaa kuin oikeat kukkaset. Eikä niissä ole ainoaakaan virhettä, ne ovat aivan säännölliset, kunhan vain eivät sula!

“Is it not clever?” said Kay, “and much more interesting than looking at real flowers. There is not a single fault in it, and the snow-flakes are quite perfect till they begin to melt.”

Vähän myöhemmin tuli Kai, kädessä suuret kintaat ja kelkka selässä. Hän huusi aivan Gerdan korvaan: — Minä olen saanut luvan laskettaa suurella torilla, missä muut leikkivät! Ja sen tiensä hän meni.

Soon after Kay made his appearance in large thick gloves, and with his sledge at his back. He called up stairs to Gerda, “I’ve got to leave to go into the great square, where the other boys play and ride.” And away he went.

Torilla köyttivät usein rohkeat pojat kelkkansa talonpojan rattaihin ja ajoivat hyvän matkaa mukana. Hauskasti se meni.

In the great square, the boldest among the boys would often tie their sledges to the country people’s carts, and go with them a good way. This was capital.

Heidän paraikaa leikkiessään tuli reki. Se oli maalattu aivan valkoiseksi ja siinä istui joku kääriytyneenä karvaiseen valkoiseen turkkiin ja päässä valkoinen karvalakki. Reki kiersi torin kahteen kertaan ja Kai sai nopeasti köytetyksi kelkkansa siihen kiinni, ja nyt hän ajoi mukana.

But while they were all amusing themselves, and Kay with them, a great sledge came by; it was painted white, and in it sat some one wrapped in a rough white fur, and wearing a white cap. The sledge drove twice round the square, and Kay fastened his own little sledge to it, so that when it went away, he followed with it.

Kulku kävi nopeammin ja nopeammin suoraan seuraavalle kadulle. Se, joka ajoi, käänsi päätään, nyökkäsi ystävällisesti Kaille, tuntui siltä, kuin he olisivat tunteneet toisensa. Joka kerta kun Kai aikoi irroittaa kelkkansa, nyökkäsi tuo henkilö taas ja niin Kai jäi istumaan. He ajoivat suoraan ulos kaupungin portista.

It went faster and faster right through the next street, and then the person who drove turned round and nodded pleasantly to Kay, just as if they were acquainted with each other, but whenever Kay wished to loosen his little sledge the driver nodded again, so Kay sat still, and they drove out through the town gate.

Nyt alkoi lunta tulla niin vyörymällä, ettei pieni poika voinut nähdä käden mittaa eteensä, kiitäessään eteenpäin. Silloin päästi hän nopeasti irti nuoran, päästäkseen eroon reestä, mutta se ei auttanut, hänen pienet ajoneuvonsa riippuivat siinä kiinni ja mentiin tuulen vauhdilla.

Then the snow began to fall so heavily that the little boy could not see a hand’s breadth before him, but still they drove on; then he suddenly loosened the cord so that the large sled might go on without him, but it was of no use, his little carriage held fast, and away they went like the wind.

Silloin huusi hän aivan ääneen, mutta kukaan ei kuullut häntä ja lumi pyrysi ja reki lensi eteenpäin. Välistä se pomppasi ilmaan, tuntui siltä, kuin se olisi kiitänyt yli ojien ja aitojen.

Then he called out loudly, but nobody heard him, while the snow beat upon him, and the sledge flew onwards. Every now and then it gave a jump as if it were going over hedges and ditches.

Hän oli aivan pelästyksissään, hän olisi tahtonut lukea ”isämeitänsä”, mutta hän ei muistanut muuta kuin ”ison kertomataulun”.

The boy was frightened, and tried to say a prayer, but he could remember nothing but the multiplication table.

Lumihiutaleet kävivät suuremmiksi ja suuremmiksi. Vihdoin olivat ne kuin suuria valkoisia kanoja. Yhtäkkiä singahtivat ne syrjään, reki pysähtyi ja se henkilö, joka ajoi, nousi. Turkki ja lakki olivat paljasta lunta. Nainen se oli, pitkä ja solakka, häikäisevän valkoinen, se oli lumikuningatar.

The snow-flakes became larger and larger, till they appeared like great white chickens. All at once they sprang on one side, the great sledge stopped, and the person who had driven it rose up. The fur and the cap, which were made entirely of snow, fell off, and he saw a lady, tall and white, it was the Snow Queen.

— Meidän matkamme on kulunut onnellisesti, sanoi hän, — mutta kuinka noin palelet? Hiivi minun karhunnahkaturkkiini! Ja hän asetti hänet rekeen viereensä, kiersi turkin hänen ympärilleen, tuntui siltä, kuin hän olisi vaipunut lumihankeen.

“We have driven well,” said she, “but why do you tremble? here, creep into my warm fur.” Then she seated him beside her in the sledge, and as she wrapped the fur round him he felt as if he were sinking into a snow drift.

— Vieläkö sinua palelee? kysyi hän ja sitten hän suuteli häntä otsalle.

“Are you still cold,” she asked, as she kissed him on the forehead.

Hui, se oli kylmempää kuin jää, se meni suoraan hänen sydämeensä, joka jo puoleksi oli jääkimpale. Tuntui siltä, kuin hän olisi ollut kuolemaisillaan. Mutta vain hetken, sitten tuntui oikein hyvältä. Hän ei enään huomannut pakkasta ympärillään.

The kiss was colder than ice; it went quite through to his heart, which was already almost a lump of ice; he felt as if he were going to die, but only for a moment; he soon seemed quite well again, and did not notice the cold around him.

— Kelkkani! älkää unohtako kelkkaani! Sen hän ensinnä muisti. Ja kelkka sidottiin erään valkoisen kanan kannettavaksi ja se lensi perässä, kelkka selässä.

“My sledge! don’t forget my sledge,” was his first thought, and then he looked and saw that it was bound fast to one of the white chickens, which flew behind him with the sledge at its back.

Lumikuningatar suuteli Kaita vielä kerran ja silloin hän oli unohtanut pienen Gerdan, isoäidin ja kaikki siellä kotona.

The Snow Queen kissed little Kay again, and by this time he had forgotten little Gerda, his grandmother, and all at home.

— Nyt et saa useampia suudelmia, sanoi lumikuningatar, — sillä silloin suutelisin sinut kuoliaaksi!

“Now you must have no more kisses,” she said, “or I should kiss you to death.”

Kai katsoi häneen, hän oli hyvin kaunis. Viisaampia, kauniimpia kasvoja ei saattanut ajatella. Nyt ei hän tuntunut olevan jäätä niinkuin silloin, kun hän istui ikkunan takana ja viittasi hänelle.

Kay looked at her, and saw that she was so beautiful, he could not imagine a more lovely and intelligent face; she did not now seem to be made of ice, as when he had seen her through his window, and she had nodded to him.

Hänen silmissään hän oli täydellinen, hän ei ensinkään pelännyt, hän kertoi hänelle, että hän osasi päässälaskua, päässälaskua murtoluvuillakin, että hän tiesi maiden neliöpenikulmat ja ”kuinka monta asukasta”, ja lumikuningatar hymyili kaiken aikaa. Silloin tuntui Kaista, ettei se, mitä hän tiesi, kuitenkaan riittänyt, ja hän katsoi ylös suureen, suureen tyhjyyteen ja lumikuningatar lensi hänen kanssaan, lensi korkealle ylös mustalle pilvelle ja myrsky humisi ja kohisi, tuntui siltä, kuin se olisi laulanut vanhoja lauluja. He lensivät yli metsien ja järvien, yli merten ja maiden.

In his eyes she was perfect, and he did not feel at all afraid. He told her he could do mental arithmetic, as far as fractions, and that he knew the number of square miles and the number of inhabitants in the country. And she always smiled so that he thought he did not know enough yet, and she looked round the vast expanse as she flew higher and higher with him upon a black cloud, while the storm blew and howled as if it were singing old songs.

Alla humisi kylmä tuuli, sudet ulvoivat, lumi säihkyili, sen yli lensivät suuret, kirkuvat varikset, mutta yläpuolella paistoi kuu suurena ja kirkkaana ja siihen katseli Kai pitkän, pitkän talviyön. Päivän nukkui hän lumikuningattaren jalkain juuressa.

They flew over woods and lakes, over sea and land; below them roared the wild wind; the wolves howled and the snow crackled; over them flew the black screaming crows, and above all shone the moon, clear and bright,—and so Kay passed through the long winter’s night, and by day he slept at the feet of the Snow Queen.

Kolmas tarina. Kukkatarha vaimon luona, joka osasi noitua

Third Story: The Flower Garden of the Woman Who Could Conjure

Mutta mimmoista oli pienellä Gerdalla, kun ei Kai enään tullut?

But how fared little Gerda during Kay’s absence?

Missä hän mahtoi olla? Ei kukaan tietänyt, ei kukaan osannut antaa neuvoja. Pojat kertoivat vain nähneensä hänen sitovan kelkkansa kiinni komeaan rekeen, joka ajoi kadulle ja ulos kaupungin portista.

What had become of him, no one knew, nor could any one give the slightest information, excepting the boys, who said that he had tied his sledge to another very large one, which had driven through the street, and out at the town gate.

Ei kukaan tietänyt, missä hän oli, monta kyyneltä vuosi, pieni Gerda itki katkerasti ja kauan. Sitten he sanoivat, että Kai oli kuollut, hän oli vaipunut jokeen, joka virtasi aivan kaupungin likellä. Oi, ne olivat oikein pitkiä, pimeitä talvipäiviä.

Nobody knew where it went; many tears were shed for him, and little Gerda wept bitterly for a long time. She said she knew he must be dead; that he was drowned in the river which flowed close by the school. Oh, indeed those long winter days were very dreary.

Nyt tuli kevät ja aurinko paistoi lämpöisemmin.

But at last spring came, with warm sunshine.

— Kai on kuollut ja poissa, sanoi pieni Gerda.

“Kay is dead and gone,” said little Gerda.

— Sitä en usko, sanoi auringonpaiste.

“I don’t believe it,” said the sunshine.

— Hän on kuollut ja poissa! sanoi tyttö pääskysille.

“He is dead and gone,” she said to the sparrows.

— Sitä en usko! vastasivat ne ja vihdoin ei pieni Gerdakaan sitä uskonut.

“We don’t believe it,” they replied; and at last little Gerda began to doubt it herself.

— Minä otan jalkaani uudet punaiset kenkäni, sanoi hän eräänä aamuna, — niitä ei Kai koskaan ole nähnyt, ja sitten menen joelle ja kysyn siltä.

“I will put on my new red shoes,” she said one morning, “those that Kay has never seen, and then I will go down to the river, and ask for him.”

Ja oli hyvin varhaista. Hän suuteli vanhaa isoäitiä, joka nukkui, pani jalkaansa punaiset kengät ja läksi aivan yksin ulos portista joelle.

It was quite early when she kissed her old grandmother, who was still asleep; then she put on her red shoes, and went quite alone out of the town gates toward the river.

— Onko totta, että sinä olet ottanut pienen leikkiveljeni? Minä lahjoitan sinulle punaiset kenkäni, jos annat hänet minulle takaisin.

“Is it true that you have taken my little playmate away from me?” said she to the river. “I will give you my red shoes if you will give him back to me.”

Ja aallot nyökkäsivät hänen mielestään niin kummallisesti. Silloin hän otti punaiset kenkänsä, rakkaimman omaisuutensa, ja viskasi ne molemmat jokeen, mutta ne putosivat aivan rantaan ja pienet kalat kantoivat ne heti hänelle maihin, tuntui siltä, kuin ei joki olisi tahtonut ottaa hänen rakkainta omaisuuttaan, koska ei sillä ollut pientä Kaita.

And it seemed as if the waves nodded to her in a strange manner. Then she took off her red shoes, which she liked better than anything else, and threw them both into the river, but they fell near the bank, and the little waves carried them back to the land, just as if the river would not take from her what she loved best, because they could not give her back little Kay.

Mutta Gerda luuli nyt, ettei hän heittänyt kenkiä tarpeeksi kauas ja niin hän kömpi veneeseen, joka oli kaislikossa, hän meni aivan äärimmäiseen päähän asti ja heitti kengät. Mutta vene ei ollut sidottu kiinni ja hänen liikkeidensä vaikutuksesta se liukui pois maalta.

But she thought the shoes had not been thrown out far enough. Then she crept into a boat that lay among the reeds, and threw the shoes again from the farther end of the boat into the water, but it was not fastened. And her movement sent it gliding away from the land.

Hän huomasi sen ja kiirehti pääsemään pois, mutta ennenkuin hän ehti takaisin, oli vene jo yli kyynärän verran vesillä ja nyt se nopeasti liukui eteenpäin.

When she saw this she hastened to reach the end of the boat, but before she could so it was more than a yard from the bank, and drifting away faster than ever.

Silloin pelästyi pieni Gerda suuresti ja rupesi itkemään, mutta kukaan ei kuullut häntä paitsi harmaat varpuset ja ne eivät voineet kantaa häntä maihin. Mutta ne lensivät pitkin rantaa ja lauloivat ikäänkuin lohduttaakseen häntä:

— Täällä me olemme, täällä me olemme!

Then little Gerda was very much frightened, and began to cry, but no one heard her except the sparrows, and they could not carry her to land, but they flew along by the shore, and sang, as if to comfort her, “Here we are! Here we are!”

Vene kulki virran mukana, hänen pienet punaiset kenkänsä uivat perässä, mutta ne eivät voineet saavuttaa venettä, joka alkoi kulkea kiivaammin.

The boat floated with the stream; little Gerda sat quite still with only her stockings on her feet; the red shoes floated after her, but she could not reach them because the boat kept so much in advance.

Kaunista oli molemmilla rannoilla, kauniita kukkia, vanhoja puita ja rinteitä, joilla oli lampaita ja lehmiä, mutta ei ihmisiä näkyvissä.

The banks on each side of the river were very pretty. There were beautiful flowers, old trees, sloping fields, in which cows and sheep were grazing, but not a man to be seen.

— Ehkäpä virta vie minut pienen Kain luo, ajatteli Gerda ja sitten hän tuli paremmalle mielelle, nousi seisomaan ja katseli monta tuntia noita kauniita, vihreitä rantoja.

Perhaps the river will carry me to little Kay, thought Gerda, and then she became more cheerful, and raised her head, and looked at the beautiful green banks; and so the boat sailed on for hours.

Sitten hän tuli suurelle kirsikkatarhalle, missä oli punainen talo kummallisine punaisine ja sinisine ikkunoineen, muuten siinä oli olkikatto ja ulkopuolella kaksi puusotamiestä, jotka tekivät kunniaa niille, jotka purjehtivat ohitse.

At length she came to a large cherry orchard, in which stood a small red house with strange red and blue windows. It had also a thatched roof, and outside were two wooden soldiers, that presented arms to her as she sailed past.

Gerda huusi heille. Hän luuli, että ne olivat eläviä, mutta ne tietysti eivät vastanneet. Hän tuli aivan likelle niitä, virta ajoi veneen suoraan maata kohti.

Gerda called out to them, for she thought they were alive, but of course they did not answer. And as the boat drifted nearer to the shore, she saw what they really were.

Gerda huusi vieläkin lujemmin ja silloin tuli talosta vanha, vanha vaimo, nojaten koukkusauvaansa. Hänen päässään oli suuri lierilakki, johon oli maalattu mitä kauneimpia kukkasia.

Then Gerda called still louder, and there came a very old woman out of the house, leaning on a crutch. She wore a large hat to shade her from the sun, and on it were painted all sorts of pretty flowers.

— Sinä pieni lapsi raukka! sanoi vanha vaimo, — kuinka sinä oletkaan joutunut suurelle, väkevälle virralle, ajautunut kauas maailmalle? Ja sitten astui vanhus aivan veteen, iski koukkusauvansa kiinni veneeseen, veti sen maihin ja nosti pois pienen Gerdan.

“You poor little child,” said the old woman, “how did you manage to come all this distance into the wide world on such a rapid rolling stream?” And then the old woman walked in the water, seized the boat with her crutch, drew it to land, and lifted Gerda out.

Ja Gerda iloitsi päästessään kuivalle maalle, mutta pelkäsi sentään hiukkasen vierasta, vanhaa vaimoa.

And Gerda was glad to feel herself on dry ground, although she was rather afraid of the strange old woman.

Рэклама