Grecko-angielska dwujęzyczna książka

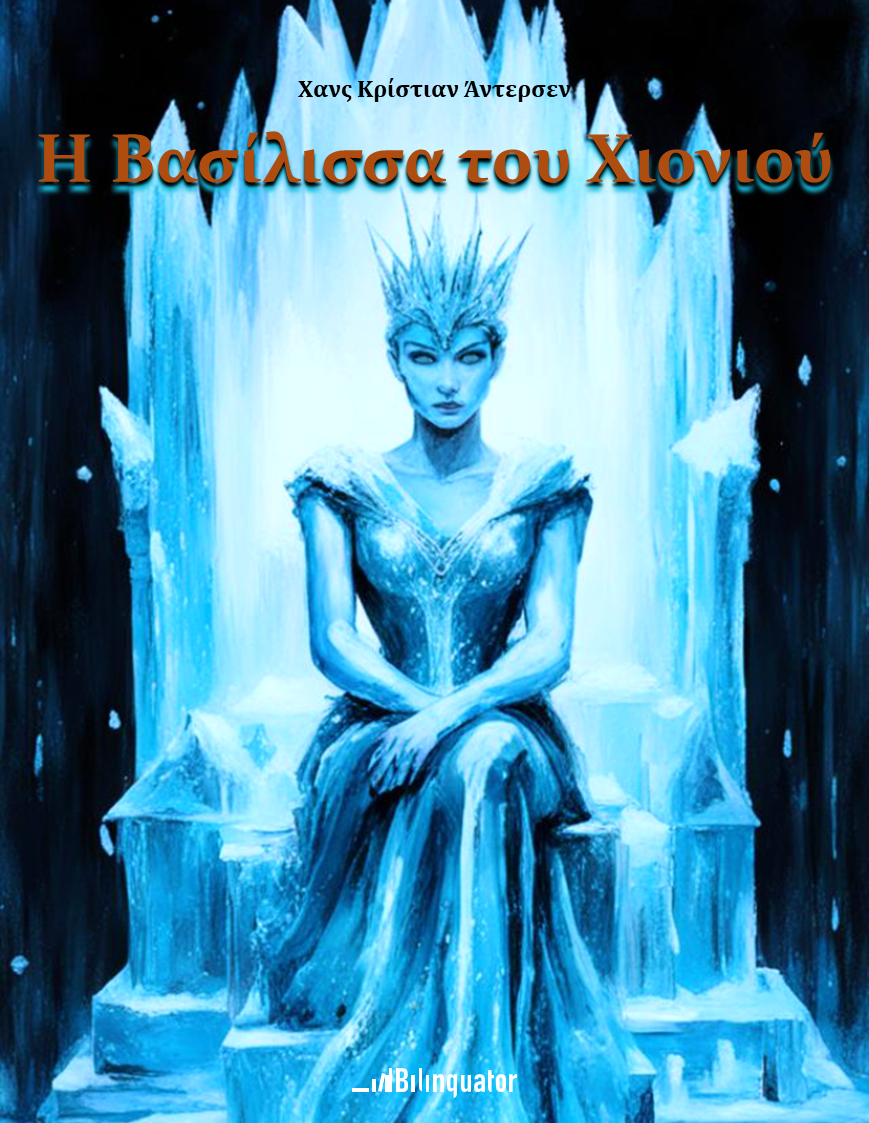

Χανς Κρίστιαν Άντερσεν

Η Βασίλισσα του Χιονιού

Hans Christian Andersen

The Snow Queen

Μετάφραση Ευαγγελία Καρή.

Translated by Mrs. H. B. Paull. With illustrations of Vilhelm Pedersen

Ιστορία πρώτη: Που Μιλά για έναν Καθρέφτη και τα Κομμάτια του

Story the First, Which Describes a Looking-Glass and the Broken Fragments

Λοιπον, ας αρχισουμε. Όταν φτάσουμε στο τέλος της ιστορίας, θα ξέρουμε περισσότερα, όμως… ας ξεκινήσουμε καλύτερα. Μια φορά κι έναν καιρό ήταν ένα πονηρό ξωτικό, κι ήταν πράγματι το πιο κακό απ’ όλα τα ξωτικά.

You must attend to the commencement of this story, for when we get to the end we shall know more than we do now about a very wicked hobgoblin; he was one of the very worst, for he was a real demon.

Μια μέρα, που είχε μεγάλα κέφια, έφτιαξε έναν καθρέφτη με δυνάμεις μαγικές: Ό,τι καλό και όμορφο καθρεφτιζόταν μέσα του, έδειχνε κακό και δυστυχισμένο, ενώ ό,τι ήταν άχρηστο κι άσχημο, η ασχήμια του μεγάλωνε.

One day, when he was in a merry mood, he made a looking-glass which had the power of making everything good or beautiful that was reflected in it almost shrink to nothing, while everything that was worthless and bad looked increased in size and worse than ever.

Τα πιο όμορφα τοπία έμοιαζαν με βραστό σπανάκι μέσα στον καθρέφτη, κι οι ομορφότεροι άνθρωποι έδειχναν τέρατα ή φαίνονταν να στέκονται ανάποδα, με το κεφάλι κάτω και τα πόδια επάνω. Τα πρόσωπά τους παραμορφώνονταν τόσο πολύ που γίνονταν αγνώριστα, κι αν κάποιος είχε μια κρεατοελιά στη μύτη, να είστε σίγουροι πως θα ‘δειχνε τόσο μεγάλη, που θ’ απλώνονταν σ’ όλη του τη μύτη, μα και το στόμα.

The most lovely landscapes appeared like boiled spinach, and the people became hideous, and looked as if they stood on their heads and had no bodies. Their countenances were so distorted that no one could recognize them, and even one freckle on the face appeared to spread over the whole of the nose and mouth.

«Σπουδαία πλάκα!» είπε το ξωτικό. Κάθε φορά που κάποιος άνθρωπος έκανε μια καλή σκέψη, ο καθρέφτης γελούσε με μια απαίσια γκριμάτσα· και το ξωτικό γελούσε με την καρδιά του με την πανέξυπνη εφεύρεσή του.

The demon said this was very amusing. When a good or pious thought passed through the mind of any one it was misrepresented in the glass; and then how the demon laughed at his cunning invention.

Όλα τα ξωτικά που πήγαιναν στο σχολείο του —γιατί είχε σχολείο ξωτικών- έλεγαν το ένα στο άλλο πως κάποιο θαύμα έγινε, και τώρα μπορούσαν να δουν πώς έμοιαζε στ’ αλήθεια ο κόσμος· έτσι νόμιζαν δηλαδή.

All who went to the demon’s school—for he kept a school—talked everywhere of the wonders they had seen, and declared that people could now, for the first time, see what the world and mankind were really like.

Πήραν τον καθρέφτη κι άρχισαν να πηγαίνουν παντού, ώσπου στο τέλος, δεν έμεινε τόπος ή άνθρωπος να μην έχει παραμορφωθεί μέσα στο γυαλί του.

They carried the glass about everywhere, till at last there was not a land nor a people who had not been looked at through this distorted mirror.

Έτσι σκέφτηκαν να πετάξουν ψηλά στον ουρανό για να σπάσουν μεγαλύτερη πλάκα. Όσο πιο ψηλά πετούσαν με τον καθρέφτη, τόσο πιο τρομακτικά γελούσε αυτός· με το ζόρι τον κρατούσαν. Πήγαιναν όλο και πιο ψηλά καθώς πετούσαν, όλο και πιο κοντά στ’ αστέρια, όταν άξαφνα ο καθρέφτης τραντάχτηκε τόσο δυνατά απ’ το χαιρέκακο γέλιο του, που έφυγε απ’ τα χέρια τους κι έπεσε στη γη.

They wanted even to fly with it up to heaven to see the angels, but the higher they flew the more slippery the glass became, and they could scarcely hold it, till at last it slipped from their hands, fell to the earth, and was broken into millions of pieces.

Έσπασε τότε σ’ εκατό εκατομμύρια κομμάτια, κι ακόμα περισσότερα, κι η δύναμή του έγινε τότε πιο κακιά και τρομερή από πριν.

But now the looking-glass caused more unhappiness than ever, for some of the fragments were not so large as a grain of sand, and they flew about the world into every country.

Γιατί μερικά απ’ τα κομμάτια, που ήταν μικρά σαν τους κόκκους της άμμου, τα σκόρπισε ο άνεμος σ’ όλο τον κόσμο, ώσπου μπήκαν μέσα στα μάτια των ανθρώπων κι έμειναν εκεί. Και τότε, οι άνθρωποι άρχισαν να τα βλέπουν όλα παραμορφωμένα, όπως ο κακός καθρέφτης, με τα δύο ή και με το ένα μάτι. Αυτό συνέβη γιατί ακόμα και το μικρότερο κομμάτι είχε την ίδια κακιά δύναμη που ‘χε ολόκληρος ο καθρέφτης.

When one of these tiny atoms flew into a person’s eye, it stuck there unknown to him, and from that moment he saw everything through a distorted medium, or could see only the worst side of what he looked at, for even the smallest fragment retained the same power which had belonged to the whole mirror.

Μάλιστα μερικά θραύσματα, χώθηκαν μέσα στην καρδιά κάποιων ανθρώπων, κι αυτοί αναρίγησαν γιατί η καρδιά τους έγινε πάγος.

Some few persons even got a fragment of the looking-glass in their hearts, and this was very terrible, for their hearts became cold like a lump of ice.

Κάποια άλλα από τα σπασμένα κομμάτια ήταν τόσο μεγάλα που τα χρησιμοποίησαν για τζάμια στα παράθυρα, και κανείς δεν μπορούσε να διακρίνει πια τους φίλους του σαν κοιτούσε από μέσα τους.

A few of the pieces were so large that they could be used as window-panes; it would have been a sad thing to look at our friends through them.

Άλλα κομμάτια τα έβαλαν στα γυαλιά της όρασης· σκεφτείτε τι τραγικό που ήταν να τα φορούν οι άνθρωποι για βλέπουν καλά και σωστά. Το κακό ξωτικό κόντεψε να πνιγεί από τα γέλια μ’ όλα αυτά, που τόσο γαργαλούσαν τη φαντασία του.

Other pieces were made into spectacles; this was dreadful for those who wore them, for they could see nothing either rightly or justly. At all this the wicked demon laughed till his sides shook—it tickled him so to see the mischief he had done.

Και τα πολύ μικρά κομμάτια του καθρέφτη συνέχιζαν να πετάνε στον αέρα· ας δούμε τώρα τι συνέβη παρακάτω…

There were still a number of these little fragments of glass floating about in the air, and now you shall hear what happened with one of them.

Ιστορία δεύτερη: Για ένα μικρό αγόρι κι ένα μικρό κορίτσι

Second Story: A Little Boy and a Little Girl

Σε μια μεγαλη πολη, όπου τα σπίτια είναι τόσα πολλά κι οι άνθρωποι ακόμα περισσότεροι, δεν υπάρχει χώρος για να ‘χουν όλοι από έναν μικρό κήπο. Γι’ αυτό, οι περισσότεροι πρέπει να αρκεστούν σε γλάστρες με λουλούδια. Σε μια τέτοια πόλη ζούσανε δύο μικρά παιδιά, που είχαν έναν κήπο κάπως μεγαλύτερο από γλάστρα.

In a large town, full of houses and people, there is not room for everybody to have even a little garden, therefore they are obliged to be satisfied with a few flowers in flower-pots. In one of these large towns lived two poor children who had a garden something larger and better than a few flower-pots.

Δεν ήταν αδέρφια, αλλά νοιάζονταν το ένα για το άλλο σα να ήταν.

They were not brother and sister, but they loved each other almost as much as if they had been.

Οι οικογένειές τους ζούσαν σε δύο σοφίτες, η μια ακριβώς απέναντι από την άλλη. Εκεί που συναντιόνταν οι στέγες των δύο σπιτιών, και η υδρορροή για τα βρόχινα νερά έτρεχε σ’ όλο το μήκος τους, υπήρχαν δύο μικρά αντικρινά παράθυρα·

Their parents lived opposite to each other in two garrets, where the roofs of neighboring houses projected out towards each other and the water-pipe ran between them.

και μ’ ένα βήμα πάνω στην υδρορροή μπορούσε να βρεθεί κανείς από το ένα παράθυρο στο άλλο.

In each house was a little window, so that any one could step across the gutter from one window to the other.

Οι γονείς των παιδιών είχαν τοποθετήσει εκεί μεγάλα ξύλινα κιβώτια και μέσα τους φύτευαν λαχανικά, μα είχαν βάλει ακόμα κι από μια τριανταφυλλιά, που μεγάλωνε κι άνθιζε ολοένα.

The parents of these children had each a large wooden box in which they cultivated kitchen herbs for their own use, and a little rose-bush in each box, which grew splendidly.

Έτσι όπως είχαν βάλει τα κιβώτια, από το ένα παράθυρο στο άλλο, έμοιαζαν σαν δύο λουλουδένιοι φράχτες.

Now after a while the parents decided to place these two boxes across the water-pipe, so that they reached from one window to the other and looked like two banks of flowers.

Τα μπιζέλια κρέμονταν από τα κιβώτια, και οι τριανταφυλλιές πέταξαν μεγάλα κλαδιά, που πλέκονταν γύρω από τα παράθυρα κι ύστερα λύγιζαν για να συναντηθούν μεταξύ τους, σαν μια θριαμβευτική αψίδα από πρασινάδα και λουλούδια.

Sweet-peas drooped over the boxes, and the rose-bushes shot forth long branches, which were trained round the windows and clustered together almost like a triumphal arch of leaves and flowers.

Τα κιβώτια ήταν πολύ ψηλά, και τα παιδιά ήξεραν πως δεν έπρεπε να σκαρφαλώνουν πάνω τους. Έτσι, έπαιρναν την άδεια για να βγουν έξω από τα παράθυρα και ν’ απολαύσουν το παιχνίδι, καθισμένα στα μικρά σκαμνάκια τους, ανάμεσα στα τριαντάφυλλα.

The boxes were very high, and the children knew they must not climb upon them, without permission, but they were often, however, allowed to step out together and sit upon their little stools under the rose-bushes, or play quietly.

Ο χειμώνας όμως ερχόταν για να βάλει τέλος σ’ αυτή τη διασκέδαση. Τα παράθυρα συχνά πάγωναν από το κρύο, γι’ αυτό τα παιδιά ζέσταιναν χάλκινα νομίσματα στη σόμπα, κι ύστερα τ’ ακουμπούσαν στο παράθυρο για να δημιουργήσουν ένα ολοστρόγγυλο ματάκι πάνω στο παγωμένο τζάμι. Κι από κει κοίταζαν έξω, το μικρό αγόρι και το μικρό κορίτσι,

In winter all this pleasure came to an end, for the windows were sometimes quite frozen over. But then they would warm copper pennies on the stove, and hold the warm pennies against the frozen pane; there would be very soon a little round hole through which they could peep, and the soft bright eyes of the little boy and girl would beam through the hole at each window as they looked at each other.

ο Κέι και η Γκέρντα.

Their names were Kay and Gerda.

Το καλοκαίρι, ένα σάλτο ήταν αρκετό για να βρουν ο ένας τον άλλο, το χειμώνα όμως έπρεπε να κατέβουν κάτω τις μεγάλες σκάλες κι ύστερα να τις ξανανέβουν πάλι επάνω· κι έξω στο δρόμο είχε το χιόνι έπεφτε παχύ.

In summer they could be together with one jump from the window, but in winter they had to go up and down the long staircase, and out through the snow before they could meet.

«Είναι οι λευκές μέλισσες» είπε η γιαγιά του Κέι για τις νιφάδες του χιονιού.

“See there are the white bees swarming,” said Kay’s old grandmother one day when it was snowing.

«Οι λευκές μέλισσες έχουν βασίλισσα;» ρώτησε το μικρό αγόρι, γιατί ήξερε ότι οι κανονικές είχαν πάντοτε από μία.

“Have they a queen bee?” asked the little boy, for he knew that the real bees had a queen.

«Ναι,» είπε η γιαγιά, «κι αυτή πετά και βρίσκει το σμήνος που κρέμεται σε παχιές συστάδες. Είναι η μεγαλύτερη απ’ όλες, και ποτέ δεν κάθεται για πολύ στη γη, αλλά πηγαίνει πάλι ψηλά στα μαύρα σύννεφα. Τις χειμωνιάτικες νύχτες, πετά συχνά στους δρόμους της πόλης και κρυφοκοιτάζει απ’ τα παράθυρα, και τότε αυτά παγώνουν μ’ έναν τρόπο, τόσο θαυμαστό, που μοιάζουν με λουλούδια.»

“To be sure they have,” said the grandmother. “She is flying there where the swarm is thickest. She is the largest of them all, and never remains on the earth, but flies up to the dark clouds. Often at midnight she flies through the streets of the town, and looks in at the windows, then the ice freezes on the panes into wonderful shapes, that look like flowers and castles.”

«Ναι, την έχω δει,» είπαν και τα δυο παιδιά μαζί· κι έτσι ήξεραν πως ήταν αλήθεια.

“Yes, I have seen them,” said both the children, and they knew it must be true.

«Μπορεί να έρθει μέσα η βασίλισσα του Χιονιού;» ρώτησε το μικρό κορίτσι.

“Can the Snow Queen come in here?” asked the little girl.

«Για άσ' την να έρθει μέσα!» είπε το μικρό αγόρι. «Κι εγώ θα την βάλω στο φούρνο για να λιώσει.»

“Only let her come,” said the boy, “I’ll set her on the stove and then she’ll melt.”

Τότε η γιαγιά τον χάιδεψε στο κεφάλι και του είπε άλλες ιστορίες.

Then the grandmother smoothed his hair and told him some more tales.

Ένα απόγευμα, όταν ο Κάι ήταν στο σπίτι και είχε σχεδόν ξεντυθεί, ανέβηκε στην καρέκλα πλάι στο παράθυρο και κρυφοκοίταξε έξω από την μικρή τρυπούλα. Μερικές νιφάδες έπεφταν, και μια απ’ αυτές, η μεγαλύτερη, στάθηκε στο χείλος μιας γλάστρας. Η νιφάδα άρχισε τότε να μεγαλώνει, να μεγαλώνει, να μεγαλώνει, ώσπου στο τέλος έγινε μια νεαρή κυρία, ντυμένη με το πιο λεπτοκαμωμένο λευκό ύφασμα, φτιαγμένο από ένα εκατομμύριο μικρές νιφάδες σαν αστέρια.

One evening, when little Kay was at home, half undressed, he climbed on a chair by the window and peeped out through the little hole. A few flakes of snow were falling, and one of them, rather larger than the rest, alighted on the edge of one of the flower boxes. This snow-flake grew larger and larger, till at last it became the figure of a woman, dressed in garments of white gauze, which looked like millions of starry snow-flakes linked together.

Ήταν τόσο όμορφη και ντελικάτη, ήταν όμως από πάγο, εκθαμβωτικό αστραφτερό πάγο! Όμως ήταν ζωντανή. Τα μάτια της κοιτούσαν σταθερά σαν δυο αστέρια, όμως μέσα τους δεν υπήρχε ούτε ησυχία ούτε ανάπαυση.

She was fair and beautiful, but made of ice—shining and glittering ice. Still she was alive and her eyes sparkled like bright stars, but there was neither peace nor rest in their glance.

Έγνεψε προς το παράθυρο κάνοντας νόημα με το χέρι της. Το μικρό αγόρι φοβήθηκε και πήδηξε κάτω από την καρέκλα, και τότε του φάνηκε πως ένα μεγάλο πουλί πέταξε έξω από το παράθυρο.

She nodded towards the window and waved her hand. The little boy was frightened and sprang from the chair; at the same moment it seemed as if a large bird flew by the window.

Ο παγετός σκέπασε τα πάντα την επόμενη μέρα, ύστερα όμως ήρθε η άνοιξη κι ο ήλιος έλαμψε, και τα πράσινα φύλλα έκαναν την εμφάνισή τους, τα χελιδόνια έχτισαν τις φωλιές τους, τα παράθυρα άνοιξαν και τα δυο μικρά παιδιά βρέθηκαν ξανά στον όμορφο μικρό τους κήπο, ψηλά στα λούκια, στην κορυφή του σπιτιού.

On the following day there was a clear frost, and very soon came the spring. The sun shone; the young green leaves burst forth; the swallows built their nests; windows were opened, and the children sat once more in the garden on the roof, high above all the other rooms.

Εκείνο το καλοκαίρι τα τριαντάφυλλα άνθισαν με ασυνήθιστη ομορφιά. Το μικρό κορίτσι είχε μάθει έναν ύμνο, που έλεγε κάτι για τα τριαντάφυλλα, και της θύμιζε τα δικά της. Τραγούδησε τους στίχους στο αγόρι, κι εκείνο τραγούδησε μαζί της:

How beautiful the roses blossomed this summer. The little girl had learnt a hymn in which roses were spoken of, and then she thought of their own roses, and she sang the hymn to the little boy, and he sang too:—

«Η τριανταφυλλιά στην κοιλάδα ανθίζει τόσο γλυκιά,

Κι οι άγγελοι κατεβαίνουν να χαιρετήσουν τα παιδιά.»

“Roses bloom and cease to be,

But we shall the Christ-child see.”

Τα δυο παιδιά, πιασμένα χέρι-χέρι, φίλησαν τα τριαντάφυλλα, κοίταξαν τη λαμπερή λιακάδα κι τους φάνηκε σα να είδαν στ’ αλήθεια τους αγγέλους.

Then the little ones held each other by the hand, and kissed the roses, and looked at the bright sunshine, and spoke to it as if the Christ-child were there.

Τι υπέροχες καλοκαιρινές μέρες ήταν εκείνες! Τι όμορφα να είσαι έξω, δίπλα στις ολόδροσες τριανταφυλλιές που δεν λένε να σταματήσουν ν’ ανθίζουν!

Those were splendid summer days. How beautiful and fresh it was out among the rose-bushes, which seemed as if they would never leave off blooming.

Ο Κέι και η Γκέρντα κοιτούσαν ένα βιβλίο με εικόνες γεμάτο τρομερά ζώα και πουλιά, όταν το ρολόι στο καμπαναριό χτύπησε πέντε, κι ο Κέι είπε:

«Ωχ, νιώθω έναν σουβλερό πόνο στην καρδιά μου, και κάτι μπήκε στο μάτι μου!»

One day Kay and Gerda sat looking at a book full of pictures of animals and birds, and then just as the clock in the church tower struck twelve, Kay said, “Oh, something has struck my heart!” and soon after, “There is something in my eye.”

Το κορίτσι έβαλε τα χέρια γύρω από το λαιμό του και το αγόρι ανοιγόκλεισε τα μάτια του, μα τίποτα δε φαίνονταν να έχει μπει στο μάτι του.

The little girl put her arm round his neck, and looked into his eye, but she could see nothing.

«Νομίζω πως έφυγε τώρα,» είπε. Όμως δεν είχε φύγει.

“I think it is gone,” he said. But it was not gone;

Ήταν ένα από κείνα τα κομματάκια του γυαλιού, από τον μαγικό καθρέφτη, που είχε μπει στο μάτι του.

it was one of those bits of the looking-glass—that magic mirror, of which we have spoken—the ugly glass which made everything great and good appear small and ugly, while all that was wicked and bad became more visible, and every little fault could be plainly seen.

Κι άλλο ένα είχε μπει κατευθείαν μέσα στην καρδιά του φτωχού Κέι, και σύντομα θα γινόταν πάγος.

Poor little Kay had also received a small grain in his heart, which very quickly turned to a lump of ice.

Δεν πονούσε πια, μα ήταν εκεί.

He felt no more pain, but the glass was there still.

«Γιατί κλαις;» ρώτησε το αγόρι. «Δείχνεις τόσο άσχημη! Τίποτα δε μου συμβαίνει, ούφ!» είπε και συνέχισε, «Αυτό το τριαντάφυλλο είναι καταφαγωμένο! Κοίτα, κι αυτό είναι θεόστραβο! Τι άσχημα που είναι αυτά τα τριαντάφυλλα! Σαν το κιβώτιο που είναι μέσα φυτεμένα!» Κι έδωσε τότε μια κλωτσιά στο κιβώτιο κι έκοψε και τα δυο τριαντάφυλλα.

“Why do you cry?” said he at last; “it makes you look ugly. There is nothing the matter with me now. Oh, see!” he cried suddenly, “that rose is worm-eaten, and this one is quite crooked. After all they are ugly roses, just like the box in which they stand,” and then he kicked the boxes with his foot, and pulled off the two roses.

«Τι κάνεις εκεί;» έκλαψε η Γκέρντα. Ο Κέι, μόλις κατάλαβε την τρομάρα του κοριτσιού, τράβηξε κι έκοψε ακόμα ένα τριαντάφυλλο, πήδηξε μέσα από το παράθυρο κι έφυγε μακριά από τη μικρή του φίλη.

“Kay, what are you doing?” cried the little girl; and then, when he saw how frightened she was, he tore off another rose, and jumped through his own window away from little Gerda.

Όταν αργότερα έφερε το εικονογραφημένο της βιβλίο, εκείνος την κορόιδεψε: «Τι απαίσια τέρατα έχεις εκεί μέσα;» Έτσι έκανε και κάθε φορά που η γιαγιά τους έλεγε ιστορίες, συνέχεια την διέκοπτε, κι όποτε τα κατάφερνε, πήγαινε πίσω της, φορούσε τα γυαλιά της και μιμούνταν τον τρόπο που μιλούσε. Αντέγραφε όλους τους τρόπους της κι όλοι γελούσαν με τα καμώματά του.

When she afterwards brought out the picture book, he said, “It was only fit for babies in long clothes,” and when grandmother told any stories, he would interrupt her with “but;”. Or, when he could manage it, he would get behind her chair, put on a pair of spectacles, and imitate her very cleverly, to make people laugh.

Πολύ σύντομα έγινε ικανός να μιμηθεί το βάδισμα και τη συμπεριφορά κάθε περαστικού.

By-and-by he began to mimic the speech and gait of persons in the street.

Ό,τι ήταν παράξενο ή δυσάρεστο επάνω τους, αυτό ήξερε πώς να μιμηθεί ο Κέι. Κι όταν το έκανε, όλοι έλεγαν:

«Αυτό το αγόρι είναι οπωσδήποτε πολύ έξυπνο!»

Όμως δεν ήταν άλλο από τα κομμάτια του γυαλιού, αυτά που είχαν μπει στο μάτι του και στην καρδιά του, που τον έκαναν να κοροϊδεύει ακόμα και την μικρή Γκέρντα, που ήταν τόσο ολόψυχα αφοσιωμένη σε κείνον.

All that was peculiar or disagreeable in a person he would imitate directly, and people said, “That boy will be very clever; he has a remarkable genius.” But it was the piece of glass in his eye, and the coldness in his heart, that made him act like this. He would even tease little Gerda, who loved him with all her heart.

Τα παιχνίδια του τώρα ήταν αλλιώτικα από πριν, είχανε τόση γνώση. Μια χειμωνιάτικη ημέρα, καθώς έπεφταν οι νιφάδες του χιονιού τριγύρω, άπλωσε το μπλε παλτό του κι έπιασε το χιόνι καθώς έπεφτε.

His games, too, were quite different; they were not so childish. One winter’s day, when it snowed, he brought out a burning-glass, then he held out the tail of his blue coat, and let the snow-flakes fall upon it.

«Κοίταξε μέσα απ’ αυτό το γυαλί Γκέρντα,» είπε. Και κάθε νιφάδα έμοιαζε μεγαλύτερη κι έδειχνε σαν ένα θαυμαστό λουλούδι ή πανέμορφο αστέρι· ήταν έξοχα να τα κοιτάζεις!

“Look in this glass, Gerda,” said he; and she saw how every flake of snow was magnified, and looked like a beautiful flower or a glittering star.

«Κοίτα, τι έξυπνο!» είπε πάλι ο Κέι. «Αυτά έχουν περισσότερο ενδιαφέρον απ’ τα αληθινά λουλούδια! Είναι ακριβώς σαν αληθινά και δεν έχουν ούτε ένα ψεγάδι επάνω τους· αν μονάχα δεν έλιωναν!»

“Is it not clever?” said Kay, “and much more interesting than looking at real flowers. There is not a single fault in it, and the snow-flakes are quite perfect till they begin to melt.”

Δεν πέρασε πολύς καιρός απ’ αυτό, κι ο Κέι ήρθε μια μέρα φορώντας τα μεγάλα γάντια του και το μικρό του έλκηθρο στην πλάτη, και τσίριξε μέσα στ’ αυτί της Γκέρντας:

«Με άφησαν να πάω έξω στην πλατεία, εκεί που παίζουν όλοι,» είπε κι έφυγε στη στιγμή.

Soon after Kay made his appearance in large thick gloves, and with his sledge at his back. He called up stairs to Gerda, “I’ve got to leave to go into the great square, where the other boys play and ride.” And away he went.

Εκεί, στην αγορά, μερικά από τα πιο τολμηρά αγόρια έδεναν τα έλκηθρά τους πάνω στις άμαξες καθώς περνούσαν, για να τους σύρουν και κάνουν μια καλή βόλτα. Ήταν τόσο σπουδαίο!

In the great square, the boldest among the boys would often tie their sledges to the country people’s carts, and go with them a good way. This was capital.

Και καθώς φούντωνε η διασκέδαση κάπως έτσι, πέρασε ένα μεγάλο έλκηθρο. Ήταν ολόλευκο και κάποιος ήταν μέσα, τυλιγμένος σ’ ένα χοντρό λευκό μανδύα ή γούνα, μ’ ένα ολόιδιο γούνινο καπέλο στο κεφάλι. Το έλκηθρο έκανε δυο κύκλους την πλατεία, κι ο Κέι πρόφτασε κι έδεσε το έλκηθρό του όσο πιο γρήγορα μπορούσε κι έφυγε μαζί του.

But while they were all amusing themselves, and Kay with them, a great sledge came by; it was painted white, and in it sat some one wrapped in a rough white fur, and wearing a white cap. The sledge drove twice round the square, and Kay fastened his own little sledge to it, so that when it went away, he followed with it.

Τρέχοντας όλο και πιο γρήγορα, έφτασαν στον παρακάτω δρόμο, και το πρόσωπο που οδηγούσε το μεγάλο έλκηθρο γύρισε στον Κέι και του έγνεψε φιλικά, σα να γνωρίζονταν. Κάθε φορά που πήγαινε να λύσει το έλκηθρό του, το πρόσωπο του έγνεφε, κι ο Κέι καθόταν ήσυχα. Έτσι συνέχισαν ώσπου έφτασαν έξω από τις πύλες της πόλης.

It went faster and faster right through the next street, and then the person who drove turned round and nodded pleasantly to Kay, just as if they were acquainted with each other, but whenever Kay wished to loosen his little sledge the driver nodded again, so Kay sat still, and they drove out through the town gate.

Το χιόνι άρχισε να πέφτει τότε τόσο πυκνό, που το αγόρι δεν μπορούσε πια να δει πέρα απ’ τη μύτη του, όμως συνέχισε, ώσπου άξαφνα άφησε το σχοινί που κρατούσε στο χέρι, για να ελευθερωθεί απ’ το έλκηθρο, μάταια όμως. Το μικρό του όχημα συνέχισε να τρέχει ορμητικά με την ταχύτητα του ανέμου.

Then the snow began to fall so heavily that the little boy could not see a hand’s breadth before him, but still they drove on; then he suddenly loosened the cord so that the large sled might go on without him, but it was of no use, his little carriage held fast, and away they went like the wind.

Φώναξε όσο πιο δυνατά μπορούσε, όμως κανείς δεν τον άκουγε. Το χιόνι έπεφτε ορμητικά, το έλκηθρο πετούσε και καμιά φορά τραντάζονταν σα να περνούσε πάνω από φράχτες και χαντάκια.

Then he called out loudly, but nobody heard him, while the snow beat upon him, and the sledge flew onwards. Every now and then it gave a jump as if it were going over hedges and ditches.

Είχε τρομάξει αρκετά και προσπάθησε να πει μια προσευχή, όμως το μόνο που μπορούσε να θυμηθεί, ήταν η προπαίδεια.

The boy was frightened, and tried to say a prayer, but he could remember nothing but the multiplication table.

Οι νιφάδες του χιονιού άρχισαν να μεγαλώνουν, να μεγαλώνουν, ώσπου έμοιασαν με μεγάλα λευκά πουλερικά. Άξαφνα πέταξαν. Το μεγάλο έλκηθρο σταμάτησε και το πρόσωπο που το οδηγούσε σηκώθηκε. Ήταν μια κυρία. Ο μανδύας και το καπέλο της ήταν φτιαγμένα από χιόνι. Ήταν μια ψηλή και λεπτή φιγούρα, εκθαμβωτικά λευκή. Ήταν η Βασίλισσα του Χιονιού.

The snow-flakes became larger and larger, till they appeared like great white chickens. All at once they sprang on one side, the great sledge stopped, and the person who had driven it rose up. The fur and the cap, which were made entirely of snow, fell off, and he saw a lady, tall and white, it was the Snow Queen.

«Ταξιδέψαμε γρήγορα,» είπε, «όμως κάνει παγωνιά. Έλα, μπες κάτω από το αρκουδοτόμαρό μου.» Και τον έβαλε πλάι της στο έλκηθρο, τυλιγμένο με τη γούνα, και το αγόρι ένιωσε σα να βυθίζεται σε μια μαλακιά χιονοστιβάδα.

“We have driven well,” said she, “but why do you tremble? here, creep into my warm fur.” Then she seated him beside her in the sledge, and as she wrapped the fur round him he felt as if he were sinking into a snow drift.

«Κρυώνεις ακόμα;» ρώτησε εκείνη και τον φίλησε στο μέτωπο.

“Are you still cold,” she asked, as she kissed him on the forehead.

Α! Το φιλί ήταν πιο κρύο κι απ’ το χιόνι και διαπέρασε την καρδιά του, που ήταν ήδη ένας παγωμένος σβώλος. Νόμισε πως θα πέθαινε για μια στιγμή, όμως αμέσως ύστερα έγινε ευχάριστο και δεν ένιωθε πια το κρύο γύρω του.

The kiss was colder than ice; it went quite through to his heart, which was already almost a lump of ice; he felt as if he were going to die, but only for a moment; he soon seemed quite well again, and did not notice the cold around him.

«Το έλκηθρό μου! Μην ξεχάσεις το έλκηθρό μου!» ήταν το πρώτο πράγμα που σκέφτηκε. Ήταν δεμένο εκεί, σε ένα από τα λευκά πουλερικά, που πετούσαν στην πλάτη του, πίσω από το μεγάλο έλκηθρο.

“My sledge! don’t forget my sledge,” was his first thought, and then he looked and saw that it was bound fast to one of the white chickens, which flew behind him with the sledge at its back.

Η Βασίλισσα του Χιονιού φίλησε τον Κέι ακόμα μια φορά, κι εκείνος ξέχασε την μικρή Γκέρντα, τη γιαγιά του, κι όποιον είχε αφήσει πίσω στο σπίτι.

The Snow Queen kissed little Kay again, and by this time he had forgotten little Gerda, his grandmother, and all at home.

«Τώρα δεν έχει άλλα φιλιά,» είπε εκείνη, «αλλιώς θα πρέπει να σε φιλήσω μέχρι θανάτου!»

“Now you must have no more kisses,” she said, “or I should kiss you to death.”

Ο Κέι την κοίταξε. Ήταν πολύ όμορφη. Καμιά πιο έξυπνη ή πιο όμορφη δεν μπορούσε να φανταστεί, και τώρα πια δεν έμοιαζε από πάγο όπως πριν, τότε που καθόταν έξω απ’ το παράθυρο και του έγνεφε.

Kay looked at her, and saw that she was so beautiful, he could not imagine a more lovely and intelligent face; she did not now seem to be made of ice, as when he had seen her through his window, and she had nodded to him.

Ήταν τέλεια στα μάτια του, δεν την φοβόταν πια καθόλου. Της είπε ότι μπορούσε να λογαριάζει αριθμούς μέσα στο μυαλό του, ακόμα και με κλάσματα, κι ότι ήξερε πόσα τετραγωνικά μέτρα ήταν όλες οι χώρες και πόσους κατοίκους είχαν, κι εκείνη γελούσε όσο της μιλούσε. Του φάνηκε τότε πως όσα ήξερε δεν ήταν αρκετά, και κοίταξε ψηλά στον μεγάλο ουρανό από πάνω τους, και πέταξαν μαζί. Πέταξαν ψηλά, πάνω από μαύρα σύννεφα, καθώς η καταιγίδα βογκούσε και σφύριζε σα να τραγουδούσε κάποιο παλιό σκοπό.

In his eyes she was perfect, and he did not feel at all afraid. He told her he could do mental arithmetic, as far as fractions, and that he knew the number of square miles and the number of inhabitants in the country. And she always smiled so that he thought he did not know enough yet, and she looked round the vast expanse as she flew higher and higher with him upon a black cloud, while the storm blew and howled as if it were singing old songs.

Πέταξαν πάνω από δάση και λίμνες, πάνω από θάλασσες κι εκτάσεις γης. Κι από κάτω τους η παγερή καταιγίδα λύσσούσε, οι λύκοι ούρλιαζαν και το χιόνι έτριζε. Από πάνω τους πετούσαν μεγάλα κοράκια κράζοντας, κι ακόμα πιο ψηλά φάνηκε το φεγγάρι, μεγάλο και λαμπερό. Αυτό απόμεινε ν’ ατενίζει ο Κέι στη διάρκεια της μεγάλης, μεγάλης χειμωνιάτικης νύχτας, και σαν ήρθε η μέρα, αποκοιμήθηκε στα πόδια της Βασίλισσας του Χιονιού.

They flew over woods and lakes, over sea and land; below them roared the wild wind; the wolves howled and the snow crackled; over them flew the black screaming crows, and above all shone the moon, clear and bright,—and so Kay passed through the long winter’s night, and by day he slept at the feet of the Snow Queen.

Ιστορία τρίτη: Για τον κήπο με τα λουλούδια της Γερόντισσας, που ήξερε από μάγια.

Third Story: The Flower Garden of the Woman Who Could Conjure

Τι απέγινε όμως η μικρή Γκέρντα από τότε που ο Κέι δεν ξαναγύρισε στο σπίτι;

But how fared little Gerda during Kay’s absence?

Πού μπορούσε να ‘χε πάει; Κανένας δεν ήξερε, κανένας δεν μπορούσε να δώσει μια πληροφορία. Το μόνο που γνώριζαν τα υπόλοιπα αγόρια, ήταν πως τον είδαν να δένει το έλκηθρό του πάνω σ’ ένα άλλο, μεγαλύτερο και θαυμαστό, που τον οδήγησε στο δρόμο και έξω από την πόλη.

What had become of him, no one knew, nor could any one give the slightest information, excepting the boys, who said that he had tied his sledge to another very large one, which had driven through the street, and out at the town gate.

Κανείς δεν ήξερε πού βρισκόταν πια. Όλοι έκλαψαν πολύ από τη λύπη τους, κι η μικρή Γκέρντα έκλαψε πικρά πολύ, ώσπου στο τέλος, πίστεψε πως πρέπει να ‘χει πια πεθάνει και πως είχε μάλλον πνιγεί στο ποτάμι που κυλούσε κοντά στην πόλη. Ω! Τι ατέλειωτα και μελαγχολικά βράδια ήταν εκείνα!

Nobody knew where it went; many tears were shed for him, and little Gerda wept bitterly for a long time. She said she knew he must be dead; that he was drowned in the river which flowed close by the school. Oh, indeed those long winter days were very dreary.

Κάποτε, ήρθε η Άνοιξη με τη ζεστή λιακάδα της.

But at last spring came, with warm sunshine.

«Ο Κέι πέθανε και πάει!» είπε η μικρή Γκέρντα.

“Kay is dead and gone,” said little Gerda.

«Δεν το πιστεύω αυτό,» είπε τότε η λιακάδα.

“I don’t believe it,” said the sunshine.

«Ο Κέι πέθανε και πάει!» είπε η Γκέρντα στα χελιδόνια.

“He is dead and gone,” she said to the sparrows.

«Δεν το πιστεύω αυτό,» είπαν εκείνα, και στο τέλος, ούτε η μικρή Γκέρντα το πίστευε πια.

“We don’t believe it,” they replied; and at last little Gerda began to doubt it herself.

«Θα φορέσω τα κόκκινα παπούτσια μου,» είπε ένα πρωί. «Ο Κέι δεν τα ‘χει δει ποτέ, κι ύστερα θα πάω στο ποτάμι για να ρωτήσω εκεί.»

“I will put on my new red shoes,” she said one morning, “those that Kay has never seen, and then I will go down to the river, and ask for him.”

Ήταν νωρίς το πρωί. Φίλησε τη γιαγιά της, που κοιμόταν ακόμα, φόρεσε τα κόκκινα παπούτσια της και πήγε μονάχη της στον ποταμό.

It was quite early when she kissed her old grandmother, who was still asleep; then she put on her red shoes, and went quite alone out of the town gates toward the river.

«Είναι αλήθεια πως εσύ μου πήρες τον μικρό μου φίλο; Θα σου χαρίσω τα κόκκινα παπούτσια μου, αν μου τον φέρεις πίσω.»

“Is it true that you have taken my little playmate away from me?” said she to the river. “I will give you my red shoes if you will give him back to me.”

Της φάνηκε τότε πως είδε τα γαλάζια κύματα να γνέφουν μ’ έναν τρόπο παράξενο. Έβγαλε τότε τα κόκκινα παπούτσια της, που ήταν ό,τι πιο πολύτιμο είχε, και τα πέταξε στο ποτάμι. Έπεσαν όμως κοντά στην όχθη, και τα μικρά κύματα τα γύρισαν αμέσως στη στεριά, λες και το ρεύμα δεν ήθελε να πάρει κάτι που ήταν τόσο ανεκτίμητο για την μικρούλα. Στην πραγματικότητα βέβαια, ήταν γιατί δεν είχαν πάρει εκείνα τον μικρό Κέι.

And it seemed as if the waves nodded to her in a strange manner. Then she took off her red shoes, which she liked better than anything else, and threw them both into the river, but they fell near the bank, and the little waves carried them back to the land, just as if the river would not take from her what she loved best, because they could not give her back little Kay.

Όμως η Γκέρντα σκέφτηκε πως έφταιγε που δεν τα πέταξε αρκετά μακριά, έτσι σκαρφάλωσε σε μια βάρκα που βρίσκονταν ανάμεσα στα βούρλα, πήγε στην άκρη και πέταξε ξανά τα παπούτσια. Η βάρκα όμως δεν ήταν δεμένη, κι οι κινήσεις της μικρούλας την έκαναν να παρασυρθεί μακριά από την ακτή.

But she thought the shoes had not been thrown out far enough. Then she crept into a boat that lay among the reeds, and threw the shoes again from the farther end of the boat into the water, but it was not fastened. And her movement sent it gliding away from the land.

Μόλις το κατάλαβε, πάσχισε να κάνει κάτι για να τη γυρίσει πίσω, μα η βάρκα είχε φτάσει κιόλας ένα μέτρο μακριά απ’ τη στεριά και γλιστρούσε γρήγορα, ολοένα και πιο μακριά.

When she saw this she hastened to reach the end of the boat, but before she could so it was more than a yard from the bank, and drifting away faster than ever.

Η μικρή Γκέρντα φοβήθηκε πολύ κι άρχισε να κλαίει, κανείς όμως δεν την άκουγε εκτός από τα χελιδόνια· κι αυτά δεν μπορούσαν να την γυρίσουν πίσω στη στεριά. Πετούσαν μόνο κατά μήκος της όχθης και τραγουδούσαν για να την παρηγορήσουν:

«Εδώ είμαστε! Εδώ είμαστε!»

Then little Gerda was very much frightened, and began to cry, but no one heard her except the sparrows, and they could not carry her to land, but they flew along by the shore, and sang, as if to comfort her, “Here we are! Here we are!”

Η βάρκα παρασύρθηκε απ’ το ρεύμα, κι η μικρή Γκέρντα κάθισε ακίνητη και ξυπόλυτη. Τα παπούτσια της έπλεαν πίσω από τη βάρκα, δεν μπορούσε όμως να τα φτάσει, γιατί η βάρκα ταξίδευε πολύ πιο γρήγορα από κείνα.

The boat floated with the stream; little Gerda sat quite still with only her stockings on her feet; the red shoes floated after her, but she could not reach them because the boat kept so much in advance.

Οι όχθες, και στις δυο πλευρές του ποταμού, ήταν πανέμορφες γεμάτες υπέροχα λουλούδια, σεβάσμια δέντρα και πλαγιές με πρόβατα κι αγελάδες· ούτε ένας άνθρωπος όμως δεν φαίνονταν πουθενά.

The banks on each side of the river were very pretty. There were beautiful flowers, old trees, sloping fields, in which cows and sheep were grazing, but not a man to be seen.

«Ίσως ο ποταμός με πάει στον μικρό μου Κέι,» είπε, κι λύπη της λιγόστεψε. Σηκώθηκε όρθια κοιτάζοντας για ώρες τις όμορφες πράσινες ακτές.

Perhaps the river will carry me to little Kay, thought Gerda, and then she became more cheerful, and raised her head, and looked at the beautiful green banks; and so the boat sailed on for hours.

Τώρα έπλεε κατά μήκος ενός μεγάλου κήπου με κερασιές κι ένα μικρό αγροτόσπιτο με παράξενα κόκκινα και μπλε παράθυρα. Ήταν αχυρένιο, και μπροστά του στέκονταν φρουροί δύο ξύλινοι στρατιώτες, και τέντωναν τα όπλα τους καθώς περνούσε κάποιος.

At length she came to a large cherry orchard, in which stood a small red house with strange red and blue windows. It had also a thatched roof, and outside were two wooden soldiers, that presented arms to her as she sailed past.

Η Γκέρντα τους φώναξε, νομίζοντας πως είναι ζωντανοί, εκείνοι όμως δεν απάντησαν όπως ήταν φυσικό. Πλησίασε κοντά τους, καθώς το ρεύμα παρέσυρε τη βάρκα αρκετά κοντά στη στεριά, και φώναξε πιο δυνατά.

Gerda called out to them, for she thought they were alive, but of course they did not answer. And as the boat drifted nearer to the shore, she saw what they really were.

Μια γερόντισσα βγήκε τότε από το αγροτόσπιτο, ακουμπώντας πάνω σ’ ένα στραβό ραβδί. Φορούσε ένα πλατύγυρο καπέλο, στολισμένο με τα πιο θαυμαστά λουλούδια.

Then Gerda called still louder, and there came a very old woman out of the house, leaning on a crutch. She wore a large hat to shade her from the sun, and on it were painted all sorts of pretty flowers.

«Καημένο παιδί!» είπε η γερόντισσα. «Πώς βρέθηκες μέσα στον μεγάλο ορμητικό ποταμό, να σε παρασύρει έτσι, μακριά στον κόσμο!» Τότε η γερόντισσα μπήκε στο νερό, έπιασε τη βάρκα με το στραβό ραβδί της, την τράβηξε στην ακτή κι έβγαλε έξω την μικρή Γκέρντα.

“You poor little child,” said the old woman, “how did you manage to come all this distance into the wide world on such a rapid rolling stream?” And then the old woman walked in the water, seized the boat with her crutch, drew it to land, and lifted Gerda out.

Η μικρούλα ήταν τόσο χαρούμενη που βρέθηκε και πάλι στη στεριά, όμως ένιωσε και φόβο βλέποντας την παράξενη γερόντισσα.

And Gerda was glad to feel herself on dry ground, although she was rather afraid of the strange old woman.

«Έλα όμως και πες μου τώρα, ποια είσαι και πώς βρέθηκες εδώ,» ρώτησε εκείνη.

“Come and tell me who you are,” said she, “and how came you here.”

Reklama