Rumuńsko-angielska dwujęzyczna książka

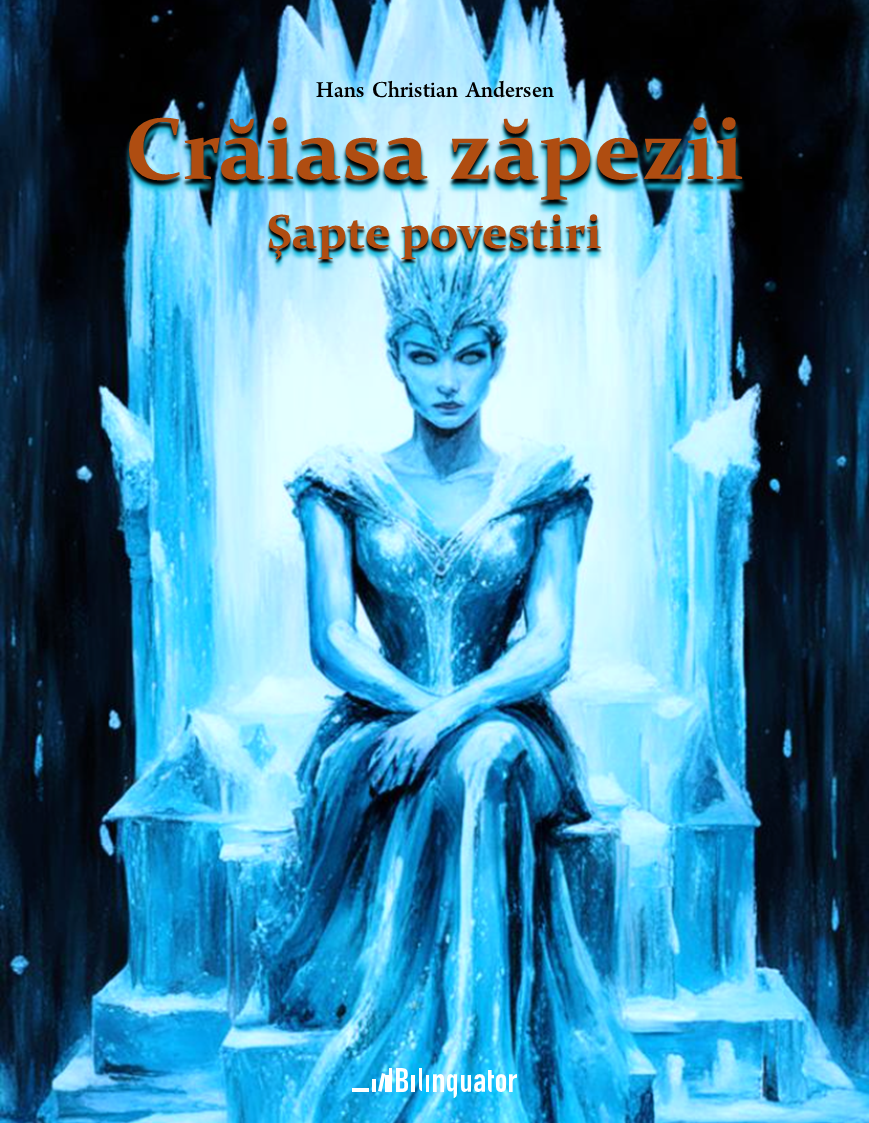

Hans Christian Andersen

Crăiasa zăpezii. Şapte povestiri

Hans Christian Andersen

The Snow Queen

Gretchen i-a spus tot. Baba asculta, dădea din cap şi zicea numai „Hm, hm!”. Şi când Gretchen a isprăvit de povestit şi a întrebat-o dacă nu l-a văzut cumva pe Karl, baba a răspuns că n-a trecut pe-acolo, dar că are să vie el, să se uite la flori, că-s mai frumoase decât toate cărţile cu poze şi fiecare din ele ştie câte o poveste.

Then Gerda told her everything, while the old woman shook her head, and said, “Hem-hem;” and when she had finished, Gerda asked if she had not seen little Kay, and the old woman told her he had not passed by that way, but he very likely would come. So she told Gerda not to be sorrowful, but to taste the cherries and look at the flowers; they were better than any picture-book, for each of them could tell a story.

Şi baba a luat-o pe Gretchen de mână şi s-a dus cu ea în casă şi a încuiat uşa după ce au intrat.

Then she took Gerda by the hand and led her into the little house, and the old woman closed the door.

Ferestrele erau foarte sus şi geamurile erau roşii, albastre şi galbene. O lumină tare ciudată pătrundea prin ele. Pe masă era o farfurie mare plină de cireşe frumoase şi Gretchen s-a aşezat şi a mâncat cireşe câte a vrut, fiindcă avea voie să mănânce cât îi place.

The windows were very high, and as the panes were red, blue, and yellow, the daylight shone through them in all sorts of singular colors. On the table stood beautiful cherries, and Gerda had permission to eat as many as she would.

Pe când mânca, baba a pieptănat-o cu un pieptene de aur şi părul s-a cârlionţat şi a căpătat o strălucire minunată, şi chipul fetiţei, rotund şi bucălat, era ca trandafirul.

While she was eating them the old woman combed out her long flaxen ringlets with a golden comb, and the glossy curls hung down on each side of the little round pleasant face, which looked fresh and blooming as a rose.

— De mult mi-am dorit o fetiţă drăgălaşă, aşa ca tine, a spus baba. Ai să vezi ce bine avem să ne împăcăm noi împreună!

“I have long been wishing for a dear little maiden like you,” said the old woman, “and now you must stay with me, and see how happily we shall live together.”

Şi tot pieptănându-i baba părul, Gretchen a uitat de prietenul ei Karl, fiindcă baba făcea farmece, dar nu era o vrăjitoare rea. Vrăjea numai aşa, ca să-şi treacă vremea şi să trăiască mulţumită. Şi ar fi vrut să rămână Gretchen la dânsa, fiindcă îi plăcea fetiţa.

And while she went on combing little Gerda’s hair, she thought less and less about her adopted brother Kay, for the old woman could conjure, although she was not a wicked witch; she conjured only a little for her own amusement, and now, because she wanted to keep Gerda.

De aceea s-a dus în grădină, a pălit cu cârja toţi trandafirii câţi erau pe-acolo şi toţi au căzut şi-au intrat în pământ, şi acuma nici nu se mai cunoştea pe unde fuseseră.

Therefore she went into the garden, and stretched out her crutch towards all the rose-trees, beautiful though they were; and they immediately sunk into the dark earth, so that no one could tell where they had once stood.

Pasămite baba se temea că Gretchen, când are să vadă trandafirii, are să se gândească la trandafirii ei de-acasă şi atunci are să-şi aducă aminte de Karl şi are să fugă.

The old woman was afraid that if little Gerda saw roses she would think of those at home, and then remember little Kay, and run away.

După asta, baba a dus-o pe Gretchen în grădină. Ce mireasmă şi ce frumuseţe era aici! Toate florile de pe lume şi din toate anotimpurile le găseai aici înflorite; nici o carte cu poze nu era mai frumoasă.

Then she took Gerda into the flower-garden. How fragrant and beautiful it was! Every flower that could be thought of for every season of the year was here in full bloom; no picture-book could have more beautiful colors.

Gretchen a sărit în sus de bucurie şi s-a jucat prin grădină până seara, când soarele s-a lăsat după cireşi; apoi s-a culcat într-un pat cu perne de mătase roşie, brodate cu toporaşi, şi a dormit şi a visat tot visuri frumoase, cum visează numai o crăiasă în ziua nunţii.

Gerda jumped for joy, and played till the sun went down behind the tall cherry-trees; then she slept in an elegant bed with red silk pillows, embroidered with colored violets; and then she dreamed as pleasantly as a queen on her wedding day.

A doua zi, Gretchen s-a jucat iar cu florile prin grădină cât a vrut. Aşa a trecut multă vreme.

The next day, and for many days after, Gerda played with the flowers in the warm sunshine.

Gretchen cunoştea acuma fiecare floare, dar, deşi era o mulţime, ei i se părea că lipseşte una. Care anume nu ştia.

She knew every flower, and yet, although there were so many of them, it seemed as if one were missing, but which it was she could not tell.

Iată însă că într-o bună zi sa uitat mai bine la pălăria de soare pe care o purta baba şi care era zugrăvită cu flori, şi a văzut printre florile zugrăvite şi un trandafir, care era mai frumos decât toate celelalte.

One day, however, as she sat looking at the old woman’s hat with the painted flowers on it, she saw that the prettiest of them all was a rose.

Baba uitase să şteargă de pe pălăria ei trandafirul atunci când surghiunise în pământ trandafirii din grădină.

The old woman had forgotten to take it from her hat when she made all the roses sink into the earth.

Dar, ce să-i faci, aşa-i întotdeauna când nu bagi bine de seamă!

But it is difficult to keep the thoughts together in everything; one little mistake upsets all our arrangements.

— Cum? a spus Gretchen. Să nu fie oare aici nici un trandafir?

Şi s-a dus repede în grădină, şi a căutat în toate straturile, dar n-a găsit nici un trandafir. Şi atunci s-a aşezat jos şi a început să plângă; şi lacrimile ei au căzut tocmai pe locul unde fusese îngropată o tufă de trandafir, şi când lacrimile calde au udat ţărâna, tufa a ieşit deodată din pământ, tot aşa de înflorită ca atunci când fusese îngropată. Gretchen a îmbrăţişat trandafirul, a sărutat florile şi s-a gândit la trandafirii ei frumoşi de-acasă şi la Karl.

“What, are there no roses here?” cried Gerda; and she ran out into the garden, and examined all the beds, and searched and searched. There was not one to be found. Then she sat down and wept, and her tears fell just on the place where one of the rose-trees had sunk down. The warm tears moistened the earth, and the rose-tree sprouted up at once, as blooming as when it had sunk. And Gerda embraced it and kissed the roses, and thought of the beautiful roses at home, and, with them, of little Kay.

— De ce m-am oprit eu oare aici? a spus fetiţa. Eu voiam să-l caut pe Karl. Voi ştiţi unde-i? a întrebat ea trandafirii. Ce credeţi, a murit?

“Oh, how I have been detained!” said the little maiden, “I wanted to seek for little Kay. Do you know where he is?” she asked the roses; “do you think he is dead?”

— Nu, n-a murit, au spus trandafirii. Noi am fost în pământ şi în pământ sunt toţi morţii, dar Karl nu-i printre ei.

And the roses answered, “No, he is not dead. We have been in the ground where all the dead lie; but Kay is not there.”

— Vă mulţumesc de ce mi-aţi spus! a zis Gretchen şi s-a dus la celelalte flori, s-a uitat în potirul fiecăreia din ele şi a întrebat: nu ştiţi unde-i Karl?

“Thank you,” said little Gerda, and then she went to the other flowers, and looked into their little cups, and asked, “Do you know where little Kay is?”

Dar florile se încălzeau la soare şi visau la ce le plăcea lor să viseze şi nici una nu ştia ce-i cu Karl.

— Degeaba mai întreb florile, şi-a răspuns Gretchen. Ele ştiu numai ce se întâmplă cu dânsele şi de altceva habar n-au!

But each flower, as it stood in the sunshine, dreamed only of its own little fairy tale of history. Not one knew anything of Kay. Gerda heard many stories from the flowers, as she asked them one after another about him.

And what, said the tiger-lily?

“Hark, do you hear the drum?— ‘turn, turn,’—there are only two notes, always, ‘turn, turn.’ Listen to the women’s song of mourning! Hear the cry of the priest! In her long red robe stands the Hindoo widow by the funeral pile. The flames rise around her as she places herself on the dead body of her husband; but the Hindoo woman is thinking of the living one in that circle; of him, her son, who lighted those flames. Those shining eyes trouble her heart more painfully than the flames which will soon consume her body to ashes. Can the fire of the heart be extinguished in the flames of the funeral pile?”

“I don’t understand that at all,” said little Gerda.

“That is my story,” said the tiger-lily.

What, says the convolvulus?

“Near yonder narrow road stands an old knight’s castle; thick ivy creeps over the old ruined walls, leaf over leaf, even to the balcony, in which stands a beautiful maiden. She bends over the balustrades, and looks up the road. No rose on its stem is fresher than she; no apple-blossom, wafted by the wind, floats more lightly than she moves. Her rich silk rustles as she bends over and exclaims, ‘Will he not come?’

“Is it Kay you mean?” asked Gerda.

“I am only speaking of a story of my dream,” replied the flower.

What, said the little snow-drop?

“Between two trees a rope is hanging; there is a piece of board upon it; it is a swing. Two pretty little girls, in dresses white as snow, and with long green ribbons fluttering from their hats, are sitting upon it swinging.

Their brother who is taller than they are, stands in the swing; he has one arm round the rope, to steady himself; in one hand he holds a little bowl, and in the other a clay pipe; he is blowing bubbles. As the swing goes on, the bubbles fly upward, reflecting the most beautiful varying colors.

The last still hangs from the bowl of the pipe, and sways in the wind. On goes the swing; and then a little black dog comes running up. He is almost as light as the bubble, and he raises himself on his hind legs, and wants to be taken into the swing; but it does not stop, and the dog falls; then he barks and gets angry. The children stoop towards him, and the bubble bursts. A swinging plank, a light sparkling foam picture,—that is my story.”

“It may be all very pretty what you are telling me,” said little Gerda, “but you speak so mournfully, and you do not mention little Kay at all.”

What do the hyacinths say?

“There were three beautiful sisters, fair and delicate. The dress of one was red, of the second blue, and of the third pure white. Hand in hand they danced in the bright moonlight, by the calm lake; but they were human beings, not fairy elves.

The sweet fragrance attracted them, and they disappeared in the wood; here the fragrance became stronger. Three coffins, in which lay the three beautiful maidens, glided from the thickest part of the forest across the lake. The fire-flies flew lightly over them, like little floating torches.

Do the dancing maidens sleep, or are they dead? The scent of the flower says that they are corpses. The evening bell tolls their knell.”

“You make me quite sorrowful,” said little Gerda; “your perfume is so strong, you make me think of the dead maidens. Ah! is little Kay really dead then? The roses have been in the earth, and they say no.”

“Cling, clang,” tolled the hyacinth bells. “We are not tolling for little Kay; we do not know him. We sing our song, the only one we know.”

Then Gerda went to the buttercups that were glittering amongst the bright green leaves.

“You are little bright suns,” said Gerda; “tell me if you know where I can find my play-fellow.”

And the buttercups sparkled gayly, and looked again at Gerda. What song could the buttercups sing? It was not about Kay.

“The bright warm sun shone on a little court, on the first warm day of spring. His bright beams rested on the white walls of the neighboring house; and close by bloomed the first yellow flower of the season, glittering like gold in the sun’s warm ray.

An old woman sat in her arm chair at the house door, and her granddaughter, a poor and pretty servant-maid came to see her for a short visit. When she kissed her grandmother there was gold everywhere: the gold of the heart in that holy kiss; it was a golden morning; there was gold in the beaming sunlight, gold in the leaves of the lowly flower, and on the lips of the maiden.

There, that is my story,” said the buttercup.

“My poor old grandmother!” sighed Gerda; “she is longing to see me, and grieving for me as she did for little Kay; but I shall soon go home now, and take little Kay with me. It is no use asking the flowers; they know only their own songs, and can give me no information.”

Şi Gretchen şi-a pus poalele în brâu, ca să poată să meargă mai repede, şi a luat-o la fugă până în fundul grădinii.

And then she tucked up her little dress, that she might run faster, but the narcissus caught her by the leg as she was jumping over it; so she stopped and looked at the tall yellow flower, and said, “Perhaps you may know something.” Then she stooped down quite close to the flower, and listened; and what did he say?

“I can see myself, I can see myself,” said the narcissus. “Oh, how sweet is my perfume! Up in a little room with a bow window, stands a little dancing girl, half undressed; she stands sometimes on one leg, and sometimes on both, and looks as if she would tread the whole world under her feet. She is nothing but a delusion.

She is pouring water out of a tea-pot on a piece of stuff which she holds in her hand; it is her bodice. ‘Cleanliness is a good thing,’ she says. Her white dress hangs on a peg; it has also been washed in the tea-pot, and dried on the roof.

She puts it on, and ties a saffron-colored handkerchief round her neck, which makes the dress look whiter. See how she stretches out her legs, as if she were showing off on a stem. I can see myself, I can see myself.”

“What do I care for all that,” said Gerda, “you need not tell me such stuff.” And then she ran to the other end of the garden.

Portiţa era închisă, dar ea a apăsat pe clanţa ruginită şi clanţa s-a ridicat, portiţa s-a deschis şi Gretchen a pornit în lumea largă, desculţă cum era.

The door was fastened, but she pressed against the rusty latch, and it gave way. The door sprang open, and little Gerda ran out with bare feet into the wide world.

S-a uitat de câteva ori înapoi, dar n-o urmărea nimeni. De la o vreme n-a mai putut merge şi s-a aşezat pe un bolovan şi când s-a uitat împrejur a văzut că nu mai era vară, era toamnă târziu; în grădina babei, în care era mereu cald şi erau flori din toate anotimpurile, nu puteai să-ţi dai seama cum trece vremea.

She looked back three times, but no one seemed to be following her. At last she could run no longer, so she sat down to rest on a great stone, and when she looked round she saw that the summer was over, and autumn very far advanced. She had known nothing of this in the beautiful garden, where the sun shone and the flowers grew all the year round.

— Doamne, cum am mai întârziat! a spus Gretchen. Uite că-i toamnă, nu mai pot să zăbovesc! Şi s-a ridicat şi a pornit iar la drum.

“Oh, how I have wasted my time?” said little Gerda; “it is autumn. I must not rest any longer,” and she rose up to go on.

Vai, picioruşele ei erau obosite şi zgâriate! De jur împrejur era urât şi frig. Crengile pletoase ale sălciilor erau galbene şi frunzele cădeau smulse de vânt şi numai porumbarul mai avea poame, dar nu erau bune. Şi când Gretchen a încercat să mănânce din ele, i-au făcut gura pungă de acre ce erau.

But her little feet were wounded and sore, and everything around her looked so cold and bleak. The long willow-leaves were quite yellow. The dew-drops fell like water, leaf after leaf dropped from the trees, the sloe-thorn alone still bore fruit, but the sloes were sour, and set the teeth on edge.

Trist şi urât era în lumea largă!

Oh, how dark and weary the whole world appeared!

A patra povestire. Un prinţ şi o prinţesă

Fourth Story: The Prince and Princess

Gretchen iar a trebuit să stea şi să se odihnească. Deodată, în faţa ei, pe zăpadă, a zărit un cioroi. Cioroiul s-a uitat la ea, a dat din cap şi a spus: „Crrr! Crrr! Bună ziua! Bună ziua!”

“Gerda was obliged to rest again, and just opposite the place where she sat, she saw a great crow come hopping across the snow toward her. He stood looking at her for some time, and then he wagged his head and said, “Caw, caw; good-day, good-day.”

Mai bine nu putea să vorbească, dar era prietenos şi a întrebat-o pe fetiţă încotro a pornit aşa, singură.

He pronounced the words as plainly as he could, because he meant to be kind to the little girl; and then he asked her where she was going all alone in the wide world.

Cuvântul „singură” Gretchen l-a înţeles foarte bine şi a priceput ce înseamnă asta. Îi povesti cioroiului toată viaţa ei şi tot ce păţise şi-l întrebă dacă nu l-a văzut pe Karl.

The word alone Gerda understood very well, and knew how much it expressed. So then she told the crow the whole story of her life and adventures, and asked him if he had seen little Kay.

Cioroiul a clătinat din cap pe gânduri şi a spus:

— S-ar putea!

The crow nodded his head very gravely, and said, “Perhaps I have—it may be.”

— Cum? Crezi că da? a întrebat fetiţa, l-a sărutat pe cioroi şi l-a strâns în braţe mai să-l înăbuşe.

“No! Do you think you have?” cried little Gerda, and she kissed the crow, and hugged him almost to death with joy.

— Încet, încet! a spus cioroiul. Cred că ştiu… cred că-i el. Da’ acuma mi se pare că de când cu prinţesa… pe tine te-a uitat.

“Gently, gently,” said the crow. “I believe I know. I think it may be little Kay; but he has certainly forgotten you by this time for the princess.”

— Stă la o prinţesă? a întrebat Gretchen.

“Does he live with a princess?” asked Gerda.

— Da, îţi spun eu toată povestea, numai că-mi vine greu să vorbesc în limba ta. Nu cunoşti limba ciorilor? Mi-ar fi mai uşor!

“Yes, listen,” replied the crow, “but it is so difficult to speak your language. If you understand the crows’ language1 then I can explain it better. Do you?”

— Nu, n-am învăţat limba ciorilor, a răspuns Gretchen.

“No, I have never learnt it,” said Gerda, “but my grandmother understands it, and used to speak it to me. I wish I had learnt it.”

— Bine, nu face nimic! Am să-ţi istorisesc şi eu cum oi putea! Şi i-a istorisit ce ştia.

“It does not matter,” answered the crow; “I will explain as well as I can, although it will be very badly done;” and he told her what he had heard.

— În împărăţia asta în care suntem acuma stă o prinţesă care e foarte deşteaptă; aşa-i de deşteaptă, că a citit toate gazetele din lume şi le-a uitat!

“In this kingdom where we now are,” said he, “there lives a princess, who is so wonderfully clever that she has read all the newspapers in the world, and forgotten them too, although she is so clever.

Deunăzi şedea pe tron şi asta pare-se că nu-i lucru plăcut, şi şezând ea aşa pe tron, a început să cânte un cântec! „De ce nu m-aş mărita?”

A short time ago, as she was sitting on her throne, which people say is not such an agreeable seat as is often supposed, she began to sing a song which commences in these words:

‘Why should I not be married?’

Chiar aşa s-a gândit ea: „de ce nu m-aş mărita? Ia să încerc!”. — Dar ea voia să găsească un bărbat care să ştie ce să răspundă când stai de vorbă cu el, unul care să şi vorbească, nu numai să şadă, arătos şi dichisit, pe tron, că ar fi prea plicticos.

‘Why not indeed?’ said she, and so she determined to marry if she could find a husband who knew what to say when he was spoken to, and not one who could only look grand, for that was so tiresome.

Prinţesa a pus să bată toba, să s-adune doamnele de onoare, şi când acestea au venit şi au auzit, au fost foarte mulţumite. „Iacă o veste plăcută, au spus ele, la asta chiar ne gândeam şi noi!”. Şi să ştii că tot ce-ţi spun eu e adevărat, a zis cioroiul; eu am o iubită, e domesticită şi stă la curte, ea mi-a povestit tot.

Then she assembled all her court ladies together at the beat of the drum, and when they heard of her intentions they were very much pleased. ‘We are so glad to hear it,’ said they, ‘we were talking about it ourselves the other day.’ You may believe that every word I tell you is true,” said the crow, “for I have a tame sweetheart who goes freely about the palace, and she told me all this.”

Iubita lui era bineînţeles o cioară. Pentru că cioara la cioară trage, asta-i ştiut, şi tot cioară rămâne.

Of course his sweetheart was a crow, for “birds of a feather flock together,” and one crow always chooses another crow.

— A doua zi, ziarele au apărut cu un chenar de inimi şi cu numele prinţesei în chenar. Scria acolo că orice tânăr plăcut la înfăţişare poate să vie la palat şi să stea de vorbă cu prinţesa şi acela care ştie să vorbească mai bine şi în aşa fel, de parcă ar fi la el acasă, pe acela prinţesa are să-l ia de bărbat.

“Newspapers were published immediately, with a border of hearts, and the initials of the princess among them. They gave notice that every young man who was handsome was free to visit the castle and speak with the princess; and those who could reply loud enough to be heard when spoken to, were to make themselves quite at home at the palace; but the one who spoke best would be chosen as a husband for the princess.

Da, da, a spus cioroiul, e chiar aşa cum zic, poţi să mă crezi, e adevărat aşa cum mă vezi şi te văd. Au venit o mulţime, era o îngrămădeală şi un du-te vino necontenit, dar nici în ziua întâi, nici în a doua nu s-a ales nimic din treaba asta.

Yes, yes, you may believe me, it is all as true as I sit here,” said the crow. “The people came in crowds. There was a great deal of crushing and running about, but no one succeeded either on the first or second day.

Toţi puteau să vorbească bine când erau pe stradă, dar de îndată ce intrau pe poarta palatului şi vedeau garda în zale de argint şi pe scări slujitori înmuiaţi în fir, şi treceau prin sălile şi galeriile palatului cu covoare scumpe şi policandre de cristal, se zăpăceau. Şi când ajungeau în faţa tronului pe care şedea prinţesa, nu mai puteau să spuie nimic decât doar cuvântul cel din urmă pe care-l rostise prinţesa şi bineînţeles că ea n-avea poftă să mai audă o dată ce spusese tot ea.

They could all speak very well while they were outside in the streets, but when they entered the palace gates, and saw the guards in silver uniforms, and the footmen in their golden livery on the staircase, and the great halls lighted up, they became quite confused. And when they stood before the throne on which the princess sat, they could do nothing but repeat the last words she had said; and she had no particular wish to hear her own words over again.

Parcă-i apuca pe toţi o toropeală cât erau în palat şi abia după ce ieşeau de acolo se trezeau şi începeau iar să vorbească.

It was just as if they had all taken something to make them sleepy while they were in the palace, for they did not recover themselves nor speak till they got back again into the street.

Şi era un şirag de oameni care ţinea de la porţile oraşului până la poarta palatului. Eram şi eu pe-acolo, a spus cioroiul. Le era sete şi foame de-atâta aşteptare, dar când ajungeau la palat nu le dădea nimeni nici măcar un pahar cu apă.

There was quite a long line of them reaching from the town-gate to the palace. I went myself to see them,” said the crow. “They were hungry and thirsty, for at the palace they did not get even a glass of water.

Unii mai deştepţi îşi luaseră câteva felii de pâine cu unt, dar nu dădeau şi altora, fiindcă se gândeau: „Las’ să fie lihniţi de foame, că dacă-i vede prinţesa aşa de prăpădiţi, nu-i alege”.

Some of the wisest had taken a few slices of bread and butter with them, but they did not share it with their neighbors; they thought if they went in to the princess looking hungry, there would be a better chance for themselves.”

— Şi Karl? a întrebat Gretchen; el când a venit? Era şi el acolo?

“But Kay! tell me about little Kay!” said Gerda, “was he amongst the crowd?”

— Stai puţin că-ţi spun îndată! A treia zi a venit un domnişor, dar nu călare, nici cu trăsura, ci pe jos; era vesel şi ochii îi străluceau ca şi ai tăi acuma, şi avea un păr lung şi frumos, dar era cam prost îmbrăcat.

“Stop a bit, we are just coming to him. It was on the third day, there came marching cheerfully along to the palace a little personage, without horses or carriage, his eyes sparkling like yours; he had beautiful long hair, but his clothes were very poor.”

— Karl era! s-a bucurat Gretchen. Bine că l-am găsit! Şi a bătut din palme de bucurie.

“That was Kay!” said Gerda joyfully. “Oh, then I have found him;” and she clapped her hands.

— Avea o raniţă în spate, a spus cioroiul.

“He had a little knapsack on his back,” added the crow.

— Nu, trebuie să fi fost săniuţa! a spus Gretchen. Şi-a luat săniuţa când a plecat.

“No, it must have been his sledge,” said Gerda; “for he went away with it.”

— Se poate, a zis cioroiul, nu m-am uitat bine, dar iubita mea domesticită mi-a spus că atunci când a intrat în palat şi a văzut garda în zale de argint şi slujitorii pe scări, înmuiaţi în fir, el nu s-a fâstâcit deloc, a dat din cap către ei şi le-a spus:

“It may have been so,” said the crow; “I did not look at it very closely. But I know from my tame sweetheart that he passed through the palace gates, saw the guards in their silver uniform, and the servants in their liveries of gold on the stairs, but he was not in the least embarrassed.

„Nu vă plictisiţi să staţi mereu pe scări? Eu mă duc înainte!”

‘It must be very tiresome to stand on the stairs,’ he said. ‘I prefer to go in.’

Sala cea mare strălucea de lumina policandrelor, curteni de tot felul umblau uşurel şi ţineau în mână ulcele de aur. Ghetele lui scârţâiau grozav, dar el nici nu se sinchisea de asta şi era ca la el acasă.

The rooms were blazing with light. Councillors and ambassadors walked about with bare feet, carrying golden vessels; it was enough to make any one feel serious. His boots creaked loudly as he walked, and yet he was not at all uneasy.”

— Sigur că-i Karl, a spus Gretchen. Avea ghete noi şi scârţâiau când umbla cu ele în odaia bunicii, l-am auzit eu.

“It must be Kay,” said Gerda, “I know he had new boots on, I have heard them creak in grandmother’s room.”

— Da, scârţâiau, spuse cioroiul. Domnişorul acela s-a dus drept la prinţesă. Prinţesa şedea pe un mărgăritar, mare cât o roată de moară. Toate doamnele de la curte cu cameristele lor şi cu cameristele cameristelor şi toţi curtenii lor şi cu slujitorii slujitorilor care şi ei, la rândul lor, aveau câte o slugă stăteau adunaţi de jur împrejur; şi cei care erau mai aproape de uşă, aceia erau mai mândri.

“They really did creak,” said the crow, “yet he went boldly up to the princess herself, who was sitting on a pearl as large as a spinning wheel, and all the ladies of the court were present with their maids, and all the cavaliers with their servants; and each of the maids had another maid to wait upon her, and the cavaliers’ servants had their own servants, as well as a page each. They all stood in circles round the princess, and the nearer they stood to the door, the prouder they looked.

Până şi sluga celui de pe urmă slujitor, care sta drept în uşă şi umbla numai cu pantofi, era atât de mândră şi înfumurată că nu-i ajungeai nici cu prăjina la nas!

The servants’ pages, who always wore slippers, could hardly be looked at, they held themselves up so proudly by the door.”

— Groaznic trebuie să mai fie! a spus Gretchen. Şi Karl s-a însurat cu prinţesa?

“It must be quite awful,” said little Gerda, “but did Kay win the princess?”

— Dacă n-aş fi cioroi, m-aş fi însurat eu cu ea, neapărat, cu toate că sunt logodit. Drăguţa mea, cioara cea domestică, zice că el a vorbit tot aşa de bine cum vorbesc eu când vorbesc limba ciorilor.

“If I had not been a crow,” said he, “I would have married her myself, although I am engaged. He spoke just as well as I do, when I speak the crows’ language, so I heard from my tame sweetheart.

Era drăguţ şi vesel domnişorul şi zicea că n-a venit să-i ceară mâna, ci numai aşa, fiindcă auzise de deşteptăciunea prinţesei şi voia să stea cu ea de vorbă. Dar după aceea şi ea i-a plăcut lui şi el ei.

He was quite free and agreeable and said he had not come to woo the princess, but to hear her wisdom; and he was as pleased with her as she was with him.”

— Da, desigur că e Karl, spuse Gretchen. Şi el e deştept şi ştie să facă socoteli în gând, cu fracţii. Nu vrei să mă bagi şi pe mine în palat?

“Oh, certainly that was Kay,” said Gerda, “he was so clever; he could work mental arithmetic and fractions. Oh, will you take me to the palace?”

— Asta-i uşor de spus, dar cum să facem oare? Am să vorbesc cu drăguţa mea, are să găsească ea ceva; pentru că să ştii că unei fetiţe aşa ca tine nu i se dă voie în palat.

“It is very easy to ask that,” replied the crow, “but how are we to manage it? However, I will speak about it to my tame sweetheart, and ask her advice; for I must tell you it will be very difficult to gain permission for a little girl like you to enter the palace.”

— Las’ că intru eu, a spus Gretchen. Când află Karl că am sosit, îndată vine jos şi mă ia cu el.

“Oh, yes; but I shall gain permission easily,” said Gerda, “for when Kay hears that I am here, he will come out and fetch me in immediately.”

— Aşteaptă-mă colo la portiţă, a spus cioroiul, apoi a clătinat din cap şi şi-a luat zborul. Abia către seară s-a întors.

“Wait for me here by the palings,” said the crow, wagging his head as he flew away.

— Drăguţa mea îţi trimite multe salutări şi îţi mai trimite şi o chiflă, a luat-o din bucătărie, au acolo destule. Ia-o, că ţi-o fi foame.

It was late in the evening before the crow returned. “Caw, caw,” he said, “she sends you greeting, and here is a little roll which she took from the kitchen for you; there is plenty of bread there, and she thinks you must be hungry.

În palat e cu neputinţă să intri, fiindcă eşti desculţă şi garda cu zale de argint şi slujitorii înmuiaţi în fir n-au să te lase. Stai, nu plânge, că tot ai să poţi intra. Drăguţa mea ştie o scară pe din dos, pe unde ajungi în iatac şi ştie unde-i cheia.

It is not possible for you to enter the palace by the front entrance. The guards in silver uniform and the servants in gold livery would not allow it. But do not cry, we will manage to get you in; my sweetheart knows a little back-staircase that leads to the sleeping apartments, and she knows where to find the key.”

Cioroiul şi cu Gretchen au intrat în grădină, pe aleea cea mare, pe care cădeau mereu frunzele din copaci, şi după ce la palat s-au stins luminile, una câte una, cioroiul a dus-o pe Gretchen la o uşă de din dos care era numai împinsă, nu închisă.

Then they went into the garden through the great avenue, where the leaves were falling one after another, and they could see the light in the palace being put out in the same manner. And the crow led little Gerda to the back door, which stood ajar.

O, cum îi mai bătea Gretei inima! Parcă ar fi vrut să facă un lucru rău şi ea doar atâta voia, să vadă dacă Karl e acolo.

Oh! how little Gerda’s heart beat with anxiety and longing; it was just as if she were going to do something wrong, and yet she only wanted to know where little Kay was.

Şi acolo era, fără îndoială! Şi ea se gândea la ochii lui limpezi şi la părul lung: parcă îl vedea cum zâmbeşte ca atunci când şedeau amândoi la umbra trandafirilor.

“It must be he,” she thought, “with those clear eyes, and that long hair.” She could fancy she saw him smiling at her, as he used to at home, when they sat among the roses.

Reklama